- Home

- Marcia Wilson

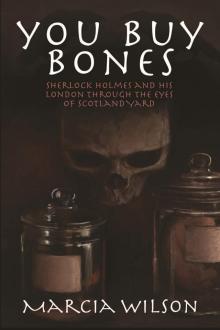

You Buy Bones Page 13

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 13

“I may have to leave for a bit, to find out the truth.” He warned. “Not now, perhaps not for a few days. I’m just... letting you know.” He wasn’t going to tell her Watson’s account. Lord, no.

Her fingers gripped his painfully. “I don’t want you to get your hopes up, Roger. But... if this is so... then... then it can only be for the good.”

Roger was mute, gripping his wife’s now-weakened hand inside his. The house had been his inheritance from his father, who had died before Elspeth. They took in roomers in summer to deal with the expenses, and he knew every long fitted plank in the floor, every inch of wall-paper and the smell of soft-coal with polish and soda. The house was their refuge and a reminder of how Elspeth’s death had changed their lives.

“I don’t want to leave you.” He warned. “If worse comes to worse, I’ll let Geoffrey take the case alone. He as much as threatened to sever me if I didn’t look to you first - and much I’d deserve it.”

“Roger, I’d be certain to let you know if things couldn’t continue without you for a bit.” Hazel leaned up and kissed him through his beard, a gesture that always made him laugh. “Is there anything I can do?”

Roger bit his lip. “I don’t know,” he said slowly. “Would the family speak with you?”

“They’ve always been willing to speak with me,” Hazel said with a coldness that was not directed at her husband at all. “I have simply chosen not to.”

Roger took a deep breath. “I need something of Elspeth’s. If you asked for it... do you think they would give it to you?”

“We can but try.” She said simply. “And we will.”

4: Take my Bones

“Heaven take my soul, and England take my bones!”

-William Shakespeare

Hazel heard someone rap at the door in the early hours of morning. Before she could even rise up, Elena was pattering down the hallway in her stocking feet. Goodness. Elena was normally a late sleeper. She wondered if the full moon was rising again; mad dogs, madmen, and Elena always reacted to the shift in the lunar cycle.

She re-settled back down under the warm quilts at the girl’s low giggles. A familiar tenor answered back. Geoffrey. Hazel smiled to herself. A week couldn’t pass without Roger and Geoffrey seeing each other. A shame they didn’t often work together.

Elena skittered back and popped her head into the sitting room. “Mum,” She beamed. “Uncle Geoffrey’s here. Has Papa left?”

“He left at a quarter-past, dear.” Hazel told her daughter - and to the entering Geoffrey Lestrade. “Elena, what are you doing up?”

“I’m trying another loaf of bread.” Elena was put out. “It’s not rising as well as yesterday.”

“There’s less warmth, sweetheart. The slower the rise the better the bread. Why don’t you take the time and create a filling to roll inside the dough when it has set? You have nearly an hour before school.”

Elena perked up and vanished as quickly as she had appeared.

Geoffrey traded a rueful adult look. “She never seems to operate under anything less than three horsepower.” He noted. “Roger’s at Bow again?”

“A late case. He didn’t give me details, save that he had to go take a lesson on the language of Flowers, even if it cost him ten shillings or seven days.” Hostess and guest shared mixed sighs. “And after that, a few telegrams, and then would see to some matters with the Bow Street Runners at the new station-house.”[32]

“Tcha! He can’t stay away! I’m lucky he spends three days at the Main Office as it is.” Geoffrey set down a paste-board box with an intriguing rattle and sank into his usual chair. “How have you been?” He asked.

“I shall be glad to get up.” Hazel said fervently. “I am tired of being tired.” She allowed her hands to twitch over the smoothly stitched fabric. “And I am close to nausea to think about sewing, or knitting, or tatting, or all of the other things.”

“How about glue?”

“Glue?”

Geoffrey opened the lid of the box and held it out. Hazel took it; the weight was more than expected. Inside rested a box of assorted shells in a wide variety. “I’ll have you know, your loving husband sent me halfway to Cheddar to pick this up.”

“Oh, bless his big awkward heart.” Hazel said with feeling. “And bless yours for being so easily swayed.”

“Swayed, bosh. You’re his sanity. That keeps me sane.” Geoffrey grinned.

“I shall make something creative.” Hazel decided. “Bring the lap-table over here.”

Geoffrey obliged; Hazel poured a handful of shells into the corner and began sorting “Geoffrey, what is this matter?” They both knew what she meant, and though she was a Northerner of the island and he from the Southern, they were both too old-fashioned and polite to mention the dead by name in a casual conversation.

Geoffrey never bothered prevaricating with Hazel. It did no good; it never did. He sighed and wished for a cigarette. “We were given some information from an unexpected source,” he spoke delicately. “It will be long and complicated, I fear. And I also fear for Roger’s well-being. But if I hadn’t included him...”

“He would have ended your friendship.” Hazel finished. “I know.” Her sharp eyes sank into his flesh like daggers. “And you have the look of someone already troubled?”

He stared at her without speaking, unsure of what to do. Long experience with Hazel finally won out. “I just...” His hands moved over the hat in his lap. “I’m already disturbed and that’s because of things that necessarily ought not to do with the case.” His cheeks pinked under his normally sallow complexion, and he stared down to give the threadbare drugget a firm examination.

“Geoffrey, you are just going to have to explain yourself now.” Hazel’s bright mind flared in the hope of something to think about.

“I’ve been studying a bit on... people with more fingers and toes than...” He cleared his throat hastily. “Than most.” That last was said out of consideration for the absent Bradstreet. “They’re called polydactyls... I thought I might fathom the motive of someone who would want to kill a child because they were so... different.” He looked further past her, from the floor to the opposing wall. “I don’t like to talk about it.”

“I shan’t think anyone would be.” Hazel answered him. “And forgive my saying so, but this already sounds dangerous. If a person would kill a child for scientific edification, they couldn’t possibly hesitate at killing a grown man.” Hazel Roane Bradstreet was a composite of all conceivable warm shades of golden browns. It made her eyes gleam like a fiercely intelligent cat’s. “A policeman would be seen as the means for such a man’s destruction. They will defend their sorry lives, Geoffrey.”

“I’m not about to let Roger stick his neck out any further than he must.” Geoffrey took a deep, deep breath as he spoke. “I am worried that he will journey into personal territory. I plan to be there at his side the entire time.”

Hazel chuckled. “Good for you, but you know as well as I do; when my Roger is in action, nothing less than a freight train can pause his motion.” At her ersatz brother’s grimace, Hazel laughed out loud. “He needs this, Geoffrey.” She sobered softly. “If this can help heal the rift in the family, he won’t hesitate. “

“The rift should have never happened.” Geoffrey snapped. “I am sorry, Hazel, I know they’re your cousins, but all of this was wrong.”

“Far cousins, thank you. But, no... Grief can take on forms as hard as a rock,” Hazel replied softly. “And one can dash themselves to death upon them. I would say the same about your own family, Geoffrey, but you seem to feel their censure is justified.”

He set his lips tight. He was not about to argue with Hazel. Not here, and especially not now, but this was their oldest argument, during which Hazel truly did sound like one of his actual sisters. Jenny, mostly... he mi

ssed her sharpest.

“And with that said,” Hazel said smoothly, “I know you will see to Roger. You’re supposed to be a bit smarter than he is... but don’t think you can persuade him of doing something if he doesn’t want to do it.”

“How well I know.” Geoffrey sighed at the ceiling. “How well I know.”

Lestrade hesitated between the hard concrete of Bow Street’s corner to Hart Street[33] and the dry awning of a tiny honey-stall. The vendor was an old veteran of the slums, a dark-skinned East Indian with foreign vowels in his speech. The men traded nods over the table of small casks and the old gentleman went back to instructing his art to a young boy in training.

The wind picked up, weak against the heavier weight of the mixed snow turning to rain. Lestrade pulled out “his” cigarette case (a beaten tin box he used for himself; the fancier one for showing amongst the social public was larger, engraved silver, and flawless). Smokers were never discouraged in these small establishments; their habit discouraged the equally filthy presence of small flying pests. The old man smiled and waved a greeting to a passing hawker bawling the mid-morning news: The end of the season’s apples and pears were nigh, but Samuel’s was happily taking orders for March’s cucumbers, spring greens and onions and Polish radishes (guaranteed sweet meat with no pith). And not to fret, dear housewives - rhubarb was on its way!

“How goes the business, Mr. Husher?”

The old gentleman beamed under his turban, his mouth a tessellation of alternate teeth. “Right enough, Mr. Lestrade. Right enough.” He finished cleaning the bit of table, and showed the boy how to drizzle a continuous stream of golden liquor into a smaller cask for selling.

Lestrade hoped Mr. Husher kept his business. Hart Street was full of illegal brothels and very enthusiastic pubs and the markets were often of low value. The Bradstreets shopped here for the safety of the children and the quality of his honey, which was pure and single-cut.

“If you wish to buy some honey, Mr. Lestrade,” Husher announced, “I have just lowered the price.”

Lestrade turned his head to study the newly-chalked slate. “A tuppence pound?” He lifted his eyebrows. “Are you that worried about the Lyle’s refinery?”[34]

Husher only smiled his crooked-path smile, his head moving from side to side (he never could quite get the British method of shaking his head). “It is a wet day, Mr. Lestrade. The honey likes the wet. I must respect my customers, for today they will buy more water than they will on a dry day.”

“Is that so? Can’t you just put it all into casks on a dry day?”

“We could, but who wants to buy honey sight-unseen?”

“Ah. True. “I’ll take a pound-cask of your wildflower.”

“Not your usual chestnut honey?”

“It isn’t for me.” His landlady would be plotting and scheming with her spring menus, and she had never quite forgiven him for 1) hating most forms of sweets and 2) liking sour treacle and bitter chestnut honey. A bribe was necessary once in a while.

He’d sheltered just in time. Smeared-up yellow-grey clouds cleared their throats and began the evening’s main performance with a sour rain that only emphasised the general dirtiness of the city. The little detective cupped his hands around his lucifer[35] and trained a wary eye on the atmospheric ceiling looming over the battered rooftops. His strong, hot breath mixed white vapour with the barely-thicker white of his tobacco. Soft lumps of rotting black snow fell from high roof-tops and burst at his feet, dislodged by the rain.

The little detective felt about as dirty as the clouds above him. Only once in his life and once in Roger’s life had they ever dealt with a personal case. Such things were not encouraged, and every sensible detective worked very hard to avoid that situation.

In his case, the end result was telling the truth and watching his own brother swing for murder as his last brother went to the madhouse. For that success, his family disowned him.

Between the two men there were some bedrock differences.

Lestrade did not question his father’s judgement. It was as simple as that.

For Roger’s case, the end result was admitting he couldn’t find his sister’s killer. For that failure, his surviving family had disowned him (The Northern pride was too stiff to take back words said in haste). Lestrade definitely, positively, and wholly questioned, criticised and disapproved that judgement. He would contemn[36] it for the rest of his life because the ostracism had been superfluous against the self-blame Bradstreet held for himself.

“Here you are, Mr. Lestrade.” The old man passed over a tiny wooden cask, clean and dry and wrapped well in clean linen sacking. “Be sure to come again. I am selling as much of the cherry-blossom honey as quickly as I can pour it. The spring coughs are troublesome.”

“I’ll keep that in mind, Mr. Husher.”

“You must be careful. Horseradish syrup and mallow-milk will keep you from getting the city in your lungs.” Like many immigrants, Mr. Husher mentally lumped all of the ills of the city under the name of London.

Bradstreet’s youngest had died coughing; pertussis passed on from someone in the outside world. Lestrade tried not to think about it... or say something sharp to the old man who meant well.

He waited a bit for the coming lull in the rain. He blew a smoke ring, mostly to see how it would behave in the heavy air. It floated awkwardly, like a bicycle tyre needing a patch, across the street until a passing cab splashed it back into vapours. A man lumbered by, either too drunk to walk right or crippled. In a veil of rising dank mist Lestrade noted and approved of a passing PC lifting his glove to the old derelict in salute. In the city of millions he was surprised to feel a stab of isolation.

Lestrade’s isolation was permanent. Nothing would bring back his brothers. For Roger the conditions had been as neat as they were cruel: Find her murderers. Find her murderers and all would be forgiven. Lestrade bowed to the inevitability of Roger’s desire to make peace with a family that didn’t deserve him, but he did hope that they would be kind to the children.

Being exiled had freed Lestrade from the day-to-day worry about his work affecting his parents. In the self-doubting hours before dawn, he sometimes wondered if it also freed them from worrying about him. Lestrade knew anger. Much of his job was spent cleaning it up. Anger was fired in origins as murky and dirty as a London fog... but its flame was bright and clean.

He onlyhoped the flame would not consume Bradstreet.

The Elegant Barley:

Getting a certain Arthur Holyrood out of his beloved work for a simple meal - even on the excuse of a private talk - was never easy. Lestrade saved up the tiny bits and favours owed before he turned his in those slips; he also kept an eye out to the schedule. This close to wages, Holyrood might be up for a free supper plate in the interests of clearing his chips.

His offer was duly accepted. They met at in a discreet corner of The Elegant Barley.

Lestrade had known Holyrood for years; he’d been a casualty PC since a skirmish with the Hooligan Gang,[37] but luckily his injuries had not completely disabled him like so many others. A good memory, honest warmth and a love of work had created his post as a specially trained doorman[38] at the Yard’s officially titled “Prisoners Property Room” better known as “back room”, “Black Room”, “Hall of Horrors”, “Collections Room”, or “Black Museum.” It was not the post for the squeamish or the superstitious, for he was neither. He was simply a man missing the full use of his left foot and neck.

Whilst appointed officers kept up the work and dealt with the public and the proper release of objects for court and investigation, Holyrood’s humble task with humbler pay was to ensure the facility was kept neat and clean, the books in place and the files in alphabetical order and the objects of murder in proper order and respectfully shown. His reduced livelihood gave him enough to live in the old inglenook of

a stone tenant building, and once a week he paid for the foodstuffs put into the community pot. At night he hired himself out to write letters for the illiterate. With tips and gratuities he had no reason to leave his posts.

Lestrade liked the man and admired his pluck, which was large enough to choke a peacock, but there was something about him the little professional found terrifying. He did not think his own will and faith was enough to keep going should his lots be cast so low. At times his enjoyment of Holyrood’s company was spoiled by this remainder, but Lestrade’s stubborn thinking caused him no end of grief when he didn’t have a case to puzzle. Holyrood was a man who found satisfaction in his work, no matter the work.

This small, lean, quiet man with thoughtful gaze and shabby clothes tended the Museum’s objects of murder intended or accidental: A horseshoe cast off by a nag had killed its owner and rested by a knife that had fatally stabbed a cook by a slip against the chopping-block. A stone a man had tripped upon to his death (the court couldn’t decide if the stone had been deliberately placed by an angry heir) tucked in a box against a child-sized bludgeon crafted by an enterprising street harlot. There were hundreds such objects and they only represented a part of the real number - which Lestrade was certain was innumerable.

These silent things harkened back to days when all acts of death were punishable by death, but who could prosecute a dumb, inanimate object that had taken a life? It had no place amongst decent people, for a thing that had human blood might grow thirsty for more. It needed to be destroyed or put away - but it couldn’t be left out or even re-used. Metal used for murder could be melted down and re-forged into a completely new implement, but the taint, the echo of death would still be there, waiting for the chance to make more crimes.

It was a sad fact for all policemen, collectors and museum curators that the mute, rusted, dust-collecting items fascinated the public. When any object had a story attached to it... someone was willing to own it. The darker the story the stronger the pull, and people stole what they wanted when they couldn’t get it honestly.

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones