- Home

- Marcia Wilson

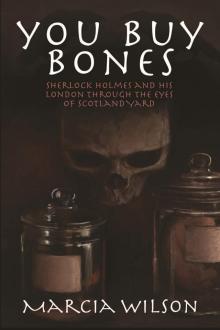

You Buy Bones Page 15

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 15

“Oh.” Holyrood relaxed and gave his cohort a reproachful snort. “Don’t scare me like that, man!”

“I didn’t think it would put a fright in you!”

“I’ve worked with the man too!” Holyrood riposted. “Didn’t you know, Sherlock Holmes in nothing less than precise speech is one of the Six Warning Signs of the Oncoming Apocalypse?”

Lestrade laughed into his collar, and the thickened mood about their table was broken.

The little man’s good humour was not lasting. He glared into his drink as if it would scry a proper future for his hopes. “I was so bloody sour at the end of it! I wanted to find the guilty, and I wanted to find the guilty amongst the carnivale. I had my reasons, mind! Who else would want to strike out at a dead man? The only people he killed were the people he worked with! He didn’t kill any of the customers, or visitors, or idle passers-by. No, it had to be a crime of science, and the Chief knew it because he didn’t let us bring in consultants. He was afraid there’d be a scandal out of it.” Lestrade looked tired at the memory. “You wouldn’t believe some of the people - and things - I encountered in that search.”

“I’m certain I wouldn’t want to.” Holyrood told him. “Fortune-tellers, Gips, the people who dabble about in things outside of the Church?”

“They’re not all bad,” Lestrade was quick to correct. “You’ve got the ones like Old Three Eyes who keeps to her own kind and keeps us alerted to any troubles.” He shrugged in that peculiar Lestradeish fashion that often perplexed his comrades. Holyrood always thought it looked like a cramped-up version of Gallic bafflement. “There you go, Holyrood! I was so caught up in that case I really was looking in the wrong direction. S’taken me what - years! - to get back on the right rail!”

“If you are right, and you do have your car on the right rail,” Holyrood assured him. “You don’t need to be told you’d best keep on your toes!” He waggled a finger. “Whoever they are, these men are dangerous. Make sure they don’t lie just to tell you what you want to hear. They’ve gotten away with this for so long... don’t think they’d hesitate to commit another one to keep it hidden.

“And watch the Crows,” the other man added in a sudden afterthought. “Most of’em are clannish - their first thoughts are for themselves and their kind!”

Lestrade agreed with his mouth, but he had already decided to trust Dr. Watson all the way in the case.

It wasn’t as though he had a lot of choice; the man had come to him after all, and unlike some people who reported a crime and then had second thoughts... Watson looked as though he knew full well what he was getting into with tattling on another member of his profession.

And his being military... a Major... well. Policemen were usually seen as unthinking beasts of the Biblical field; the serving staff that kept the Home Office a well-oiled machine. Most of Watson’s ilk wouldn’t have given a copper so much as the proper time.

But Watson was giving the Yard respect.

The Yard owed him nothing less than the regard they gave the public... but they also owed the young man a good sight more because of the way he treated them in turn.

Lestrade respected the complications that rose in such a breast as Watson’s. Doing the right thing wasn’t easy when you were taught there were different kinds of right and wrong. In the bottom of the well rested the truth: This was wrong and needed to be corrected.

The detective turned to the rest of his fish and conversation as they moved on to more pleasant things - ending on a friendly note - as his mind was already in another direction, thinking hard: The miserable Ambisinister’s case had closed as a failure. If he could only close it... find some answer to the missing limb.

It wouldn’t hurt his reputation at all, but behind the shell of professional vanity lurked a more human selfishness: It stung his pride as a young and eager policeman that the killer’s body had not gone to rest intact.

The Police force had many advantages to it, if a man was willing to make the sacrifice. It was a meritocracy, so if a man didn’t advance he was swiftly dismissed. Lestrade did not see himself as growing old, but he had no family and he had precious few friends. If he was rendered helpless he didn’t want to finish his life destitute in a gutter.

If this case could help him track down Carney Ambisinister’s missing hand, it would help him close a chapter on his past... and put his own personal wolf at bay just a bit longer.

“...I said, are you finished for the day?”

Lestrade rescued his wits in the nick of time. “Near enough. I promised Brother Jerome I’d stop by tonight.”

Holyrood made a face better suited on an ogre’s. “Mind your step on that street.” He muttered.

“It isn’t that bad, man.”

“It isn’t so good either!”

Bow Street:

Mr. Bradstreet was so tired he hung up his coat and thought to himself, Hazel’s laughing. Oh, good. A moment later his treacle-filled brain asserted, and he was hustling down the short hallway to the cramped sitting room.

His wife was sitting up, a small lap-desk of shining things before her, and swatting at the grasping hands of their daughters. “Get away, I told ye! My word, it’s no wonder the sponge had t’be punched down again! You need to pay attention to what ye started!”

Another swat as a narrow hand inched to the tray. “Mr. Bradstreet! Tell your daughters to keep their grasping little hands to themselves or go hire out as pick-pockets!”

“What’s all this then, ladies?” Roger growled deep in his beard. “Are you being plaguesome again?”

“Plaguesome, pestiferous, and penitent-less!” Hazel exclaimed. “Tell them to go see to that bread!”

Roger recoiled. “Me tell a woman what to do in the kitchen?”

“It is my kitchen.”

“You heard the Queen, girls.” He tagged them on their heads as they grumbled past; when he grinned back at Hazel, his eyes were shining. “I see Geoffrey got the box.”

“Do I want to know how you came about this?” Hazel was a generous person, but giving her something in return was a problem; she was full of restrictions and brooked no tolerance for something that was too frivolous, too expensive, too troublesome, or too sentimental.

“It was simple. I had Geoffrey pick up a box of assorteds the last time he was sent to the coast. He didn’t even have to pay anything; he says he traded a box of cigars for the lot.”

“They’re lovely.” Hazel held up a stickpin. Tiny green pea-shells had been glued together to form a small stalk and three oval leaves. “This only wants a flower-head to go with it. What do you think?”

“Mmmn... How about something early? A snowdrop or a rosebud?”

“A rosebud it shall be.” Hazel set to work. “This should answer all the worries you men have on spilling water inside your pockets when we go dancing!”

“Better make one for Geoffrey too.” Roger advised.

“Hmph. He’s a better dancer than you, Roger, and he’s got a twisted foot!” Hazel scolded almost absently as she picked through the shells. “A small cowry,” he heard her mutter. “That’s what I need...”

Paddington Street:

Lestrade pulled out his case-notes as soon as he built up the fire. A contrary crack at his sill made his desk chilly; perfect for keeping a bottle of cider. He set his chair by the grate and was into another hour of study when the door rattled from the knock of a large knuckle and Roger popped in head-first, snow and ice melting on his face.

“Thank you, old fellow.”

“Not at all.” Lestrade twisted around. “What are you doing on this end at this hour? It’s a bit late for work. Come in by the grate; you’re all nithered!”

“Ah, right.” Bradstreet eyebrowed a droll look at what was on Lestrade’s desk, and his friend half-scowled at him, half-daring him

to produce a large, Gilbert and Sullivan-style musical on his own habit of bringing his desk home on his back. “I just came to give you the new news.” He settled himself into the guest chair whilst Lestrade, without asking, rose to dig out the flask behind the book-end. “Got a telegram. The evidence that Dr. Watson asked for will be delivered to us by post by the end of the week.” The information was met with a grunt and a nod. “Geoffrey, you have a distracted, dowie air about you.” He noted the little book at the corner and picked it up, turning it over and over.

“I’m sorry, Roger. I just feel like this is going to be hell on ea - oh, put that down,” Lestrade said hastily. “Horrid little thing.” He muttered. “Where was I... Oh, I was feeling like this is going to be hell on earth.”

“I don’t feel, I know.” Bradstreet tutted and frowned at the book. “What’s the matter with a book of doctors?”

“They’re specialists. Horrid stuff. Pictures of men of science posing with skulls... and... model heads and... and glass eyes... and... and things like that. And I do not like the fact that we not only have to work with a civilian in this, but we have to allow him to take some personal risk. The Chief will not approve when he reads this in the report.”

“What are you reading all that slop for?” Bradstreet wanted to know.

“There’s a picture of our suspect in there...”

“And you think I shouldn’t take a look at him?”

Bradstreet’s voice was patience itself. A bad sign.

Lestrade puffed out his breath, flushed at his friend’s knowing look, and picked up the book again. “Here you are...” He grumbled, and opened it, but clearly forced himself to let Bradstreet hold it in his own two hands.

The big Runner stared deep into the glossy paper, trying to see God Knew What on the other side of the ink. It did not escape Lestrade’s notice that his friend’s pulse had quickened, nor that he was making the effort to breathe calmly.

“He looks...” Bradstreet hesitated, but there was no getting around the truth. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more harmless-looking man in my life! He looks more harmless than the priest who baptised me!”

“If that’s the same Pastor Jones on your wall, that’s harmless indeed.” Lestrade felt depressed. He leaned back in his chair and stared at the ceiling above his nose.

Bradstreet ground the image into his brain with about fifteen seconds of intense staring, his face without any expression, and handed back the book. Lestrade clapped it shut and stuffed it into a drawer.

“Problem?” Bradstreet queried coolly.

“It’s got me edgy.” Lestrade told him with a perfect lack of shame. “I’m not used to it. To them those are all just... tools. And like any man with a tool, they’ll take it out and show it off like a workman would a new brass hammer, or... or a garden spade.”

“Ay, but they were human once, and there is a part of them that is human still.” Bradstreet said softly.

“Yes. I’m all sickish inside, Roger.” He wanted to pace, but his tiny room wouldn’t allow it. He clasped his fingers together instead, and ground his palms together.

Neither man spoke for a minute.

“Don’t read that book, Roger.” Lestrade said at last. “Please.”

“I promise.”

Lestrade lit a cigarette from his personal tin and (since they were friends) threw the tin at Bradstreet. “Back to our conversation... I honestly can’t think of Watson as a civilian. If anything, he thinks we’re the civilians.” His mouth bent around his smoke at the purpled indignity of Bradstreet. “Once a Major, always a Major, and I’ll bet you money, marbles, and chalk that if he didn’t hold his medical profession to be higher, he’d be still using his military title.”

Bradstreet grumbled as he leaned forward to light his smoke off Lestrade’s. “Still...”

“Oh, I understand completely.” Lestrade leaned back. “But he’s no civilian. And as far as risks go, you’ve seen what Jezails can do to a human body.” He put his hands in his pockets as Roger puffed, and stared out the window.

“Well, then, what’s bothering you if it isn’t the fact that we’ll be employing the only human being that can make a human being out of Sherlock Holmes?”

Lestrade snorted softly. “Fancies.” He said curtly.

“I’m glad I’d already swallowed.” Bradstreet stared as his drink struck the little table. “Geoffrey, the word is exclusive of you. You have no imagination.”

“For which I’m grateful. I don’t need an imagination.” Lestrade did not mention that his nightmares might possibly qualify as imagination, but he didn’t like to think of them either. He pulled his hand out and stared at his nails. “I’ve been going over the old tales of the Selkies... Watson seems to think they’re important.”

“You’re in a bad mood because you’re reading fancies?”

“No... No, that has nothing to do with it. I don’t see these things as anything more than... colourful, muddled, and side-tracked reports.” Lestrade rubbed at his forehead slowly. “Have you ever looked at a fairy tale, Roger, really, really looked at it?”

“Every day. Especially when I’m interviewing a suspect for mental evaluations.”

“Well... I’m starting to see some of these fairy tales as... a very muddled account of things that really happened. Oh, I don’t believe for one moment that humans can turn into seals!” He lifted his hand. “But I’ve been pretending I was examining these accounts for Scotland Yard.”

“Go on.” Bradstreet urged. “You’ve gotten my curiosity.”

“The old accounts call the Selkies, Finmen, from Finland, which even the old writings say is actually the Orkneys. The people from those islands were a mixture of Greenlanders, Nords, and sea-faring travelers that wandered by. The men and women were both capable of using those skin boats to travel on.” “Lestrade picked up a page and read from it:

“It may be thought wonderful that they live all that time and are able to keep to sea so long... His boat is made of seal-skins, or some kind of leather; he also has a coat of leather upon him, and he sitteth in the middle of his boat, with a little oar in his hand, fishing with his lines.

“And when in a storm he seethe the high surge of a wave approaching, he hath a way of sinking his boat, till the wave passes over, lest thereby he should be overturned.”

Bradstreet listened with both ears. He tugged on his left moustache. “It sounds like the way a seal swims... The kayaks of those Greenlanders would behave in that manner. I’ve seen them flip upside down just to make the visitors squeal. Those skin togs of theirs leave’em high and dry and grinning every time.”

“That’s what I thought. One thought led to another.” Lestrade put the paper down. “The Finmen were blamed for bad seasons; I suppose that’s strategic sense. If you’ve going to go out for fish, you’ve got to be in their own element, and someone in a skin boat can certainly go where a large craft can’t.” He was looking increasingly uncomfortable. “What do you recall of those old stories?”

Bradstreet shrugged awkwardly. “They aren’t stories I’d tell the children... they’ll hear them soon enough... Mostly the old tales everyone seems to know about: That if you take the skin of a Selkie woman, she’ll have to stay with their land-man and be their wife. Most of them did stay, and bore children, but even years later, when the fisherman carelessly let her find out about the location of her skin, she’d steal it back and return to the waves.”

“Mmn-hmn.” Lestrade held his eyes. “What if that skin of the Selkies is actually the skin that’s hung over the wooden frame of their single boats... and their waterproof clothing that lets them get out into that frozen waste?”

Bradstreet slowly turned the numbers over in his head. His eyes widened a little. “It would make sense.” He blinked. “Perfect sense.”

Lestrade poured himsel

f another drink. “Well, there’s no proof...”

“Huh. That circumstantial evidence is strong enough to hang the Brothers Grimm!” Bradstreet huffed. “The polydactyl trait must hail from a Greenlander with that trait; probably a poor woman who was kidnapped by someone who wanted a hard-working wife who didn’t speak enough of his language to ask for help.” Bradstreet snorted. “No fashing wonder the explanation is all about seals.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Geoffrey, have you ever had to deal with a missionary or three moving in? The first thing he does is pull out a pen and start “transcribing the quaint customs of the area.” Bradstreet pulled a long face.

Lestrade copied him. “Yes. It seems like the Church recruits an awful lot of would-be scientists.”

“And have you ever seen anyone play the game for their own amusement?”

“Many times. The old people would tell those priests all sorts of things - outrageous things you couldn’t possibly believe, and they’d dutifully write them down as if it were Gospel - pardon the accidental pun.”

“Not at all. It’s a perfect pun. I’m just thinking that a fairy tale about a fairy wife can be overlooked. Kidnapping a bride can’t be.”

Lestrade flinched as if a bolt had hit him. “It happens.” He snapped.

A moment later, Bradstreet remembered who he was talking to and could have kicked himself. Damn. It might be a blessing to have extensive family records... but bad stories were inevitably with the good ones.

The Runner fervently kept talking to move things along. “I’m thinking I need to start looking at Garrett’s reading.” He said aloud. “Lad’s too caught into the fanciful stuff as is.” He set his glass down with a sigh. “And speaking of reading... will your desk be clear in a few days?”

“Absolutely.” Lestrade answered. A bit of tension bled out of him. He sighed. “When your correspondence comes in, we’ll talk to Watson.”

“Speaking of fanciful... how’s he going to keep this particular little problem away from Mr. Sherlock Holmes?”

“Lord only knows; I don’t.” was Lestrade’s fervent reply.

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones