- Home

- Marcia Wilson

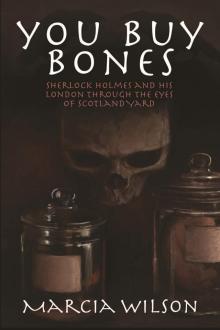

You Buy Bones Page 3

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 3

Holmes threw himself backwards into a chair (ignoring a book in the back), his eyes glowing like unholy little lamps as he pressed his fingertips together. Lestrade encountered his most unsettling sensation yet, for the man was thinking, to the point that Lestrade could feel him thinking. Just a bit harder, and he would hear those cogs grinding.

“Mr. Frogge, for all his commonality, was a Continental of the first water,” Holmes mused. “And he came from a distinguished family of proud chemists, some of who developed or assisted in the development of many drugs we use today.” His thin lips twitched. “My expertise comes from a natural interest in organic chemistry, you see. It was inevitable that we would meet one day on the battlefield.”

“I take it there was no love lost.” Lestrade guessed with no effort.

“Perhaps in a way.” Holmes’ smile grew wider, and it resembled a silent snigger. “He did feel flattered enough at my attention that he promised to find a way to poison me personally. I’m sure he would have, were he not so caught up in a contract with Merck.”

“Did you speak to the Yard over that?” Lestrade was shocked.

“No proof, Mr. Lestrade. No proof - no bother.”

Lestrade stared as the threat of premature death merely washed over the young man.

“Back to your little paper... it was mostly likely a diary page. The man kept a log of his more intriguing compounds. But as to what the substances were...” He pursed his lips together thoughtfully. “Frogge kept to the German standards of extracts. Wolf’s Milk is the English translation for Solomon’s Seal. The plant is graceful yet otherwise unremarkable... but the small rhizomes have a sweetish flavour when tasted, and the German peasant still holds the belief that a wolf will dig up the root and eat it when he suffers damage in battle.”

“Solomon’s... seal?” Lestrade pulled out his notebook and wrote it down, thinking that he had earned his own fee for tonight.

“Devil’s Milk, I fear, will give you more trouble. It is a generic word for several different plants in the Euphorbia name, commonly known as spurge, all marked with the ability to week an acrid and thick white sap or latex when wounded. What the Devil has to do with it, I’m certain I have no idea, but I should like to find out some day.” He puffed slightly, remembering he had a pipe. “None of the plants that I know of that description are meant to be taken internally. Dandelion has been called Devil’s Milk on occasion, but no one hears of a dandelion poisoning. No, if this is a case for poisoning, look to the bottle of Euphorbia on his cabinet. If it is a case of a general tonic, I would say go no further than the patch of dandelion in his salad-bed. Either way you shall come to a conclusion.”

His pipe recalled, Mr. Holmes regarded its stem. “Frogge was attached to the plants that could kill as easily as they could heal. If he was using Euphorbia, then I would suggest one should look at the clients who were being treated for skin-cancers. The sap’s use in dissolving the blemishes are well known. He may have even treated them successfully, assuming they never roused his unpredictable temper and led him to throw his terrible additives into his potions.” Grey eyes flitted over Lestrade again. “He was a man of his pride, our late Mr. Frogge. To his peculiar way of thinking, death by using a man’s own medicine against him was in truth the Hand of Justice.”

Dazed beyond the grip of speech, Lestrade found himself standing under a street-lamp like a common loiterer. He was actually sweating.

What had just happened? He was a policeman, an Inspector... and if anyone was supposed to be upset and off-balance it shouldn’t be him!

No wonder Roanoke sent him in his place. This Holmes character - and a man who was overly blessed with character if there ever was one - was like no one in his life. He flushed again to remember the little ways he’d been embarrassed by the man. His clothing, his ill appearance, his own name...

And yet the man - or youth - or some muddled-up combination of the two - had figured out what had taken Roanoke hours. That quickly he’d put it in his mind, and his mind had tossed out the answers.

“Take this to Mr. Sherlock Holmes of Montague Street, but don’t tell him what I suspect. If he comes to the same conclusion, then we’ll know I’m right.”

Lestrade rubbed the back of his neck, thinking. They had all sorts of consultants working for the Yard, but damned if he’d ever seen one like this.

Well, he was rude even if he was smart, but Lestrade could notice things too. All that mental showing-off had to have been from all that reading scattered about the room... and it was clear that given a choice between a book and a meal, the book would win.

Aesthetic, was it? People starved themselves for different reasons. He didn’t completely respect those who had the means for food and didn’t take care of themselves. But the way that man nipped about, there was a chance he actually forgot to eat once that brain took over.

Plants that heal, plants that kill. He wasn’t so unfamiliar with them... Good Lord. England was crawling with poisonous plants. But that idea that something that could kill could also heal was familiar too.

Something bitter could be something sweet in the long run, if it helped cure an unpleasant condition.

The thought came to him then, in that weak puddle of light, and he started laughing whilst the homeless man in the gutter wondered if he should call for a Bobby.

A bitter substance for a sweet outcome.

One might as well describe Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

7 Despite the plentiful derogatory judgments on these immigrants, the police (often puzzled over their customs) noticed a much lower rate of domestic violence and murder than felt typical of the London poor. (From p. 19-20 POLICING THE GHETTO: JEWISH EAST LONDON, 1880-1920 DAVID ENGLANDER

8 A particularly unpleasant and deadly fog.

An Ordinary Meeting

1881:

It would be years before Sherlock Holmes condescended to refer to Lestrade as ‘the best of professionals’ and for now the real crown was bestowed upon Gregson for being the smartest of the Yarders. This honour would be as digestible (and chewable) as a cocklebur salad were it not for the fact that Holmes was only speaking the truth. Truth, as the lowliest policeman knew, had a habit of being nasty, and even if they didn’t know from Mr. Holmes’ observations... Gregson would be sure to remind them of their inferiority against his brain.

Lestrade also believed without evidence that Gregson’s enviable solve-rate had to do with the fact that most people took one look at the flinty-eyed boulder in a suit, the jaw that sought exercise by testing the strength of an oncoming fist, and his own fists, which, when compressed together, looked like a bony football... and decided to co-operate with everything the man wanted in terms of a confession. Some were so helpful, they were willing to make things up as they told their side of the story.

Despite the charm of the pin-striped package that was Gregson, Lestrade was passionately annoyed at his rival for other reasons. Mostly... Gregson really was smarter. By quite a lot.

He was even smarter than the Chief, but proving again how smart he was, he never let slip this interesting fact. As opposed to Lestrade, who seemed to get in trouble with the Chief on a daily-to-weekly-to-monthly basis without using any of his smarts at all.

There were days when Lestrade hated them both.

He felt like a tiny cairn terrier up against Gregson - and often acted like it because if anything was guaranteed to make his temper hare off without him, it was too-smart, too-smug visages dripping with worthless compliments and even more worthless bits of ‘advice.’

Gregson knew this.

And flaunted it lavishly.

“Still moping over the forgery case?”

Lestrade stopped eating his fish long enough to tilt his head up, sewing his mouth shut against any foolish words that might want to come out. It was just habit. And oh, joy

s, Gregson caught him in a private moment with supper in the Elegant Barley. “Not moping so much as annoyed.” He admitted to the big man. “What are the odds of both experts on type dropping dead in the same week?”

“In a city of millions?” Gregson decided to pretend Lestrade was actually asking him. “Not too bad, actually. And since they were father and son?” Not too bad on top of that. Add a cracked well-casing too close to the street renovations downhill from the new sewage culvert - and the odds seem bettable to me.”

So. Gregson knew about it. “Is that even a word?” He asked waspishly.

Gregson smirked. “Try reading once in a while. You’d be amazed at what happens when your eye goes over all those little black shapes on paper.” He paused, just as Lestrade was mentally corking his impulses with a chunk of fried haddock. “And don’t tell me you don’t have time to read, Lestrade. If you move your eyes really quick, you can catch some of a news-story before the oil bleeds through.”

Lestrade thought of throwing his supper in his rival’s face, but damned if he was going to name his termination of service after Gregson.

Because, annoying as Gregson could be (and he was tops), he still had to keep something in storage for when he consulted with Sherlock Holmes.

After Holmes moved to his admittedly better rooms on Baker Street, Lestrade’s first reaction was to give a private little groan. He still ached from the Break-bone fever[9] that had wasted a good third of the Force, and it was too early to be back on his feet. Holmes’ old lodgings at least had the convenience of a respectable tavern where he could pause afterwards and wash the taste of being outdone by the amateur in about eight gills[10] of the best Grozet in London. His mother had always sworn by a regular dose of Grozet[11] to chase away the plagues in the arteries - she wouldn’t have thought it would be her son’s salvation as an ulcer preventative. But - Baker Street being in the opposite direction from the Malmsey Keg[12] - Lestrade had a very soldierly attitude to the lots life had thrown to him.

He would just have to find another, equally comfortable shift in his life. And so he paid his calls to Sherlock Holmes, private consulting detective and bona fide slight madman.

His resolution that was assured the first time he met the housekeeper. She was a stamp above the last, slightly gin-perfumed matron of Montague Street. A proper lady, Lestrade was glad to doff his hat to someone who could pay him the respect of looking him in the eye - and he had a feeling her cooking would be trusted (Mr. Holmes’ refusal to notice food might have kept him alive more often than not when he was at her address).

“Mind you to always knock before you go up, sir.” She told him kindly. This was indeed a change from the last housekeeper, who operated under the hope that someday the Suspicious Mr. Lestrade would take her difficult lodger off her hands with a pair of Derbies. “Mr. Holmes is an excitable enough fellow.”

“You don’t say, Mrs. Hudson.” Lestrade’s acting skills were largely underappreciated.

“And then of course, there’s the poor doctor.”

Lestrade’s arm locked up in the act of hanging his hat on the coat-tree. For a moment his own expression (sallow and ill from the epidemics), goggled back at him in the mercury-backed mirror. He’s completely gone mad, then? Was his first thought - Holmes has finally finished due process of mental law.

“Yes, a good young man, and a decent lodger, but his nerves have been shattered, Inspector.” Mrs. Hudson skewered him with her eyebrows. “Maiwand.”

Lestrade was shocked. “Maiwand?” He breathed.

“Aye, sir. Wounded badly enough to be sent back to us, and took the fever on the way. Do be so kind and do nothing that would upset him.” Mrs. Hudson took his coat with the casual efficiency of those who know their own business better than anyone else’s. “Shall I bring up a cup of tea?”

“Well... thank you; that would be most kind.” Lestrade’s thoughts swirled like dry leaves in the gutter as he ascended the steps. Dear me, Sherlock Holmes sharing rooms - with a war veteran at that? He didn’t know which portion was more unbelievable.

He paused at the open door and saw the long legs propped on the ottoman before the rest of him. He knew at a glance this was not Holmes’ whipcord, skeletal energy. A step further and the man glanced up from his reading with a pleasant smile illuminating the pallor of long illness. Despite the blue-tinged pallor and the hollowed cheeks, he was completely ordinary looking; Lestrade was relieved, as if someone had to have some tangible abnormality to prove their desire to spend more than two hours with Sherlock Holmes. Come to think of it, that’s the most ordinary-looking man I’ve ever seen. He’s all shades of brown - hair, eyes, skin, shoes and clothes! He could be a model for the everyman in the Strand.

“Good-afternoon.” The man asked in a pleasant enough voice; it was trained and modulated to affect a variety of tones for the occasion, but there was something under the ‘r’ that spoke of the soft, low burr of the Queen’s Scots. “May I help you, sir?”

“Good-afternoon, sir.” (When in doubt... touch your brow, his father would say... but Lestrade was made of sterner stuff, and lifted his hand on the premise of doffing off his hat for the second time in as many minutes.) “Mr. Lestrade. I am here to see Sherlock Holmes.”

The man quirked up a thick eyebrow like a gun cocking back.

Yes, Scottish. Lestrade thought. No other race in the world can do... that.

“I’m afraid he’s stepped out for a bit, but he might come back soon. Would you like a cup of tea whilst you wait?”

“Thank you, your housekeeper has already offered.” Lestrade took a glance in the room and noted the walls ruefully. “Well, it didn’t take him long...” He muttered under his breath.

The man had heard. “I can’t imagine what his rooms were like off Montague Street.” He put his book aside and leaned forward to offer his hand. “Dr. John Watson at your service, Mr. Lestrade.”

“And I at yours.” The hand was bone-thin but firm, a short-lived strength until he recovered his natural reserves. This man is terribly ill, the copper noted. Lestrade knew for himself that particular leanness was unnatural. This body should be bigger and broader; he didn’t carry himself with the power of a small man had. Though the face was friendly enough, open as a bowl, it was because of force of will and a defiant confidence, not from a vapid lack of character.

There was a look to his eyes, though, that a man on the Force would recognise: Eyes of a veteran. Eyes of nightmares and walking ghosts.

The recognition went both ways, Watson seeing Lestrade knew, and knowing Lestrade was similar in mind. It drove Lestrade to look away and around the walls again. “I say, did he leave you any room for your belongings?

Watson threw back his head with a laugh.

“I came with little enough,” He chuckled. “Save my life and some of my health.” Humour glittered in those dark brown eyes - the liveliest part of him. “And a few insignificant vices, to which I reserve for my full attention once I’m back on my figurative feet.”

Lestrade chuckled softly. “I do understand. I’m still labouring under the latest epidemic of London. A part of me can barely believe I’m out and about.”

“Are you certain you should be?” Watson tilted his head to one side thoughtfully. His eyes were bald and scorching with their simple cut-to-the-core gaze. “If you don’t mind my saying so, though you are an improvement over my own self.”

“That’s a fine way of putting it, but yes. My work makes no allowance for such things as a three-week holiday.”

“Ah.” Watson’s face was rueful. “If it weren’t for the wound pension holding penury at bay, I’d be saying the same.” He shrugged, both knowing the wound pension was a daub in the eye as far as keeping poverty at bay. “Not that there’s much call for an ill physician!” He lifted that wry eyebrow again. “I used to teach the finer points of handguns to

men going into Infantry... somehow I think that would not inspire confidence in my abilities as a surgeon either.” He accepted it philosophically.

Scot without a doubt. They’re as eloquently ironic as the Irish, but - thankfully - stoic as the figurative stone. I don’t think I could bear an Irishman in the same room as Holmes.

“Well if you must be about, keep drinking fluids. Water if you trust in its cleanliness; broth, juice - stay away from milk in all forms. That could just make it worse.” Watson had found Ship’s tobacco and began packing away a methodical blackthorn pipe.

“I thought milk was supposed to be good for what ailed.” Lestrade blinked, thinking of the milky hot teas of his childish days.

Watson winced slightly as he put the tobacco on the table - or perhaps it was the strain on a stiff shoulder as he pushed aside a small box of bullets? “The last thing a sick man needs is more mucus.”

“Well, I’m not going to argue with that - unless you tell me I have to foreswear my evening pint. Then we’ll have words and I’ll take back my fee.”

Watson grinned at him, and despite the fact Lestrade thought he was dreadfully young to be a doctor, he was struck by the core of strength glimpsed inside. “Be sensible in your pints, sir. Elderberry ale would be best in your condition.”

“Never heard of it.” Lestrade confessed. “I’m a Grozet man myself.”

“Then you should have no sacrifice of your morals.” Watson blew smoke - not easy to do because he was still smiling. “It’s a heather brew of elderberry fruit and flower. There’s nothing better for getting the immune system going - naturally I’d recommend a tincture or syrup, but I’ve found ale goes down a bit fairer.” His lips twitched. “And it’s one-twentieth the price.”

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones