- Home

- Marcia Wilson

You Buy Bones Page 5

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 5

He’d probably serve again, too. Lestrade thought back to that eerily ordinary looking man. They’d underestimated him; that was obvious. He’d placed his bet on Watson simply out of some misplaced sense of contrariness to balance out the careless judgement of his comrades. But Watson had shown the stuff of his being during that Hope case... Following Holmes quietly, keeping his distance, never speaking out of turn - his memory must be phenomenal to string so many details of the crime into logical points. His notes progressed as naturally as beads on a string.

He’s a clever one, Lestrade scowled. For the most part, quiet, showing manners when Holmes forgets his; and then jumping into action without a second to spare. If he hadn’t put his part in with Hope, someone would have been sailing out that window! And then when he put his hand on Hope’s chest... Lestrade hadn’t expected to feel any of the softer emotions on Hope’s behalf. But the look on Watson’s face had drawn him close to it. Watson was a soldier who didn’t hesitate, but he placed a high enough value on life to regret its impending loss.

I cannot believe he is rooming with Sherlock Holmes... But for how much longer? It was a good thing Lestrade’s expenses were paid up for the month; he suddenly didn’t hold hope that he’d win his pound back on the 30th.

Lestrade lived in in one of the small flats carved out of a still-dignified if threadbare stone Regency rectangle just off Paddington Station. He could just barely claim “Paddington Street” as his address; his trod was a narrow road built over a derelict rail-line used to freight goods to the now-abandoned warehouse two buildings down. It had been part of the Station’s original territory for a very brief period in the city’s history.

His Paddington Street was a small, barely-mapped artery connected to the beating heart of the Station, one of the busiest places in the entire city. Lestrade liked being so close to a place where the old blended with the new, and there was still a schoolboy’s glee at living by the world’s first underground railway. He never quite lost his thrill at travelling under the city. To be honest, he also liked being in one of those many places in London that was old yet overlooked by most cartographers.

Once in his flat he paused and put his back against the door with a sigh. The hubbub of London muffled against the walls, an underwater sound mixed with the upstairs stench of the Elder-Johnson’s linseed oil and paints (if only he could accept the less obnoxious water-colours of Johnson-the Son, but artists seemed to be a quarrelsome lot even within their family). A wet-linen coil of steam from the Harpers crept out of the basement at his side. Home, sweet home.

He really lived a fair trot from Number Four Whitehall, but the rooms were too decent to give up. He had his bedroom and a study, and Mrs. Collins provided supper and the promise he was not disturbed by the other tenants. A shame no one ever thought of recruiting feisty old widows for law enforcement. Then again, her stern moral vertebrae probably prevented more up and coming young careers in mischief than he would ever arrest.

The Inspector groaned to himself and pulled his shoes off, replacing them with his indoor shoes (slippers were for people who were never called out of the house at a second’s notice). One more hour and he was certain of blisters. Off went his jacket and loose went the tie. His collar, stiff with starch that morning was now stiff with sweat and soot. He pulled it off with a shudder of relief and let it join the growing stack of the week’s wash (Harper’s of course).

No evening for Grozet. Very well. Now that Gregson wasn’t around to prod his conscience - Lestrade could not bring himself to agree to everything that fat-handed, flaxen-haired man said or did - he could do a little detective work on his own. It wasn’t as though it would be the first time he’d brought his work home.

Some minutes later he was ensconced in his study with a pot of cock-a-leekie cooling by increments at the one window. Mrs. Collins’ ratter trotted in, found no rodents for killing, and settled down on top of his feet with a self-important sigh. Lestrade automatically moved the small stack of papers out of the terrier’s way as he lit a cigarette. At his wrist was a pad of paper and several pencils. Time to get to it. Watson himself admitted I took accurate notes. We’ll see if he has cause to rue that observation.

1) Sherlock Holmes

2) Dr. Watson

3) T.G.

4) G.L.

Less than an hour and three sheets of foolscap later, Lestrade had come to the following points:

One: Sherlock Holmes was written about, for good or ill, more than anyone; Holmes had by far the longest and most elabourate list of sins. The Yard detectives were portrayed as petty and jealous and barely educated at their worst, but that didn’t exactly compare to the horror of a mental image of a grown adult sulking in a chair wreathed in tobacco smoke and complaining about bizarre mental phenomenon... beating the corpses with a stick?

Two: Anyone doubting Holmes’ mental balance was out of true would just have to read this out and see for themselves. His destiny was clearly written on the madhouse. Mrs. Hudson must be getting more than the usual rent on her lodgers. Sherlock Holmes was without a doubt the worst roomer in God’s Grey London.

That last point went far in re-establishing some of Lestrade’s original sense of sympathy for the doctor. He could well imagine the spiritual and psychic agony of being forced to invalid inaction in a small room with a man who scraped his bow across his violin - a perfectly good Strad - as he thought.

He and Gregson were a bit tougher, but Watson seemed to have made even points with them. For everything disparaging against them (and the Yard) Holmes would slip some inadvertent comment that could be taken as back-handed praise. I wonder if Holmes was educated by nuns...? The thought was an attractive one.

As supper steamed to a palatable level, he figured out some of what bothered him. It was Watson’s own self-portrayal. Lestrade easily recalled his experience with the man, and whilst he couldn’t sense the doctor was lying about himself, there was still something greatly off-tune about it.

‘The campaign brought honours and promotion to many, but for me it had nothing but misfortune and disaster.’

Now why does that statement strike off? Lestrade scowled, trying to reconcile that compound sentence with his impression of the man. Granted, he didn’t really know him outside of that first meeting, and then there was the actual case, but...

But I was paying attention to him; Lestrade’s abashed enlightenment went down about as well as a mouthful of spoiled Darjeeling. I was watching him as well as Holmes. But if you look at this... Watson barely existed when we were talking... Sloppy detective work.

Lestrade tapped his way down the list.

“Gregson is the smartest of the Scotland Yarders... he and Lestrade are the pick of a bad lot. They are both quick and energetic, but conventional - shockingly so. They have their knives into one another, too. They are as jealous as a pair of professional beauties. There will be some fun over this case if they are both put upon the scent.”

No, that wasn’t flattering by a long chalk, but the implications did not escape Lestrade - at least not this time. Holmes was dead-on accurate, and Watson recorded it neatly.

The pick of a bad lot. There were good men outside the usual rings of corruption, but... Lestrade’s head throbbed. It was a pleasant change from that feeling in his gut. We’ll never live down the Turf Scandal...

Holmes is portrayed by Holmes’ own words, and by his room-mate’s own words. I swear, I never thought of Holmes being vain, but he has the right of it. He’s also right that Holmes has mixed feelings about notoriety.

And Watson... Watson writes from the perspective of a ghost. That is queer. For some time Lestrade pondered the list he’d written out, his pencil tapping on the paper. Solutions failed to present. There were too many pieces left separate, like looking at a jigsaw puzzle badly scattered and trying to see the theme of the assembled piece.

Fina

lly, he got up and made his way to the shelf for something to drink with the soup. But first... Lestrade put his pencil to the calendar. “Today Gregson learned what speechless felt like.”

Lestrade took his holiday with mixed feelings. The Yard was still up in arms - and when was it not - although not for the usual reasons involving crime, malcontents, public disturbances and that extremely large but well used category known as “vice.” A three-day weekend meant one thing to Lestrade’s mind. Rest. After weeks of running himself about, he could finally lie down and sleep until his own body wanted to wake up.

His plan worked until two cab drivers decided to quarrel over the same fare at the top of their lungs under his window. Lestrade fumbled for his watch and blearily peered at the numbers. Finally, he closed one eye and focused on the facing. Six? He groaned and pulled the covers off his shoulders.

The air was warm but Lestrade knew better than to trust it. The smell of the Thames echoed the movements of the weather over the water. It would not be a perfect day forever. He donned his heavy coat but left it open for the sun and yawned his way down the street. Street urchins scattered like quail; he ignored them, knowing the lot on Paddington Street was fairly well-behaved - at least they were to him. There were several streets where his small size translated to “fair game” to the future dissatisfied residents of London.

“Morning, Inspector!” Constable Perkins lifted a hand the size of a coracle paddle in greeting. Lestrade was amused to note that whilst the Paddington urchins flew before him like small insects, they flowed around Perkins as though the policeman was a large and rather tough boulder. “Are you headed to ‘Bart’s then?”

Lestrade slowed his step, hands in his pockets (off duty after all). “‘Bart’s?” He repeated slowly. “Wasn’t planning on it. Why, is something happening? If Holmes is trying to tattoo the corpses again I don’t want to know about it...

Perkins blanched. “I’m sorry, sir, I thought someone would have let you know.” Up close the dark smears of sleeplessness were clear under his pale blue eyes. “Constable Lions was injured in the line of duty.”

“Lions?” Lestrade sucked in his breath. Lions had been assisting Bradstreet on a notorious baby-farm practice.

“Yes, sir. They were storming the building where the bodies were hid, sir, and it was quite old and run-down. Lions was last in line; they think his weight was what did it after everyone else’s, and he went right through, into that wretched basement. Cut himself open on a broken billhook, sir. Doctors aren’t sure if he’ll have the use of his leg back.”

Lestrade closed his eyes for a moment. Lions was young but coolheaded. He was calmer than even many of the old-timers at the Yard. He did not know if the man could face debility with the same attitude. He also did not want to think of Lions suffocating or breaking his own spine in a convulsion of lockjaw.

“Thank you for telling me, Constable.” Lestrade said finally. “I’ll pass on to him that you were concerned.”

Perkins flushed, awkward at praise. “Not at all, sir. We stick together.”

“Yes...” Lestrade thought of Gregson. “That we do, Constable.”

Lestrade grabbed up a sausage roll from a vendor and as an afterthought, stuffed another into his coat. He ate the one on his way to ‘‘Bart’s, his mood not improved by the fate of another Constable.

Why didn’t Punch talk about how dangerous it was to be a policeman?

Punch was popular because of its reputation for sticking to “inoffensive” material, but the truth was, there was no such thing as a gentle ribbing when it came to such a serious matter. Policemen, plain or uniformed, were at risk as soon as they stepped into the street, and that risk did not go away when they went home. They weren’t paid enough to put up with half the lot they did, and on top of the people who were willfully trying to cause them harm, there was the problem of London itself.

London was not safe.

That great cesspool, Watson had called it. True, that. He shuddered to think of what would happen to that ‘cesspool’ analogy once the Thames started warming up and people conducted housecleaning on everything from garbage to dead animals and even churches were known to toss unwanted bodies into the river to make room for the more affluent. The Wharves were pulsing, malignant organisms, and people disappeared every night - men, women and children. They also disappeared in both directions. Gregson was killing himself trying to prove the resurgence of the shanghai trade off the East side, but so far it was going no further than the slave market over on Bethnel Green.

Lestrade didn’t bother with wondering at Lions’ ‘accident’ as it was no accident. Buildings that sheltered crime were deliberately kept squalid, and a Bobby could face getting hit by a tripwire, snare, or doctored-up pitfall as fast as a bomb laced with poison. Fifty years ago, entire portions of London had been populated with nothing but criminals. It had caused a level of crime to match the last time England had been invaded by the enemy. Those desperate hours had created Sir Peel’s MPF, but the problem had only subverted, going from brazen to subtle to controlled and intelligent. It had taken years whilst even the magistrates had held the Peelers in contempt, but they had done the job, and made Charing Cross safe.

Well... as safe as any part of London.

No, there was precious little in the way of assistance for the police. If there was, they wouldn’t have to resort to consulting with people like Holmes.

And he does help, but Great Heavens he is arrogant with it! Lestrade caught himself fuming, and controlled it with a grimace. Enough. He would be visiting a comrade. Lions was married, wasn’t he? Lestrade turned the possibility over in his mind. His wife - Marianna? - she’d be worried. He set his steps eastward.

‘Bart’s had been in practice since around 1137, but Lestrade doubted a single family who stretched that far back would be so friendly. He passed a placard in the hallway advertising the local clinics throughout London and the purpose of each - and almost stumbled in his tracks when he saw that the card read “If you cannot read this, ask someone on duty to read it for you.” It left him a shade more disillusioned than he’d woken with that day. Must’ve gotten someone from the Home Office to do it...

Constable Lions was a big man - should he survive to become a plainclothes Inspector he’d make a formidable figure. Even in a room surrounded by the bed-ridden, he stood out with his bushy black mane and beard. Most nocturnal Constables grew beards to keep warm and prevent ‘colds in the throat’ as per the wishes of the Department, but Lions’ was a proud mane of curly India ink that was only defeated by the crowning glory of an equally lavish collection of locks (Gregson swore he had William Teach in the family). The loss of blood made his skin very white as he sat propped up with a newspaper, and he looked up with pleasure at his visitor.

“Well, good-morning, sir. I hope you aren’t here to convalesce too.”

“Not at all.” Lestrade shook his head at the lump under the blanket. There were obviously a great many bandages underneath the left leg. “But I’m surprised they put you in a room all to yourself.” He nodded to the ‘walls’ of the room, which was nothing more than four hanging white sheets that reeked of one of those hospital ward chemicals - the sort of stuff that would trim out your nostrils. “Have you been promoted?”

Lions blushed at the mild frivolity. “Not at all, sir. It’s just that several of the doctors, well... there was a bit of a fuss over me when I came in, and I suppose you could say there was a fight.”

“A fight?” Lestrade pulled his coat off and sank into the one chair - obviously brought in for the consulters. “What kind of fight?”

“I’m not really sure, sir. Except I don’t mind telling you I’m never playing a game of tug o’ war at the family reunions ever again. I know what the rope feels like now.” Lions blushed even further. “There was this new doctor, fresh out of surgery from somewhere, trying to say m

y leg would have to come off. Then this second doctor, he comes in and he’s younger than the first one, and he says - pardon me, sir - bloody hell no one’s getting amputated on my watch, and they started shouting in the hallways - oh, thank you, sir.” Lions took Lestrade’s sausage roll.

“Go on, lad, you seem to have had the livelier night.” Lestrade leaned forward on his knees. “I take it the argument was resolved for the best?”

Lions chewed and swallowed. “Not in so many words, sir. A new’un came in off the street, still in his walking-clothes and his stick, and took a look at the two fighting, and the mess I was making on the floor, and sent me to the back surgery.” Lions suddenly guffawed. “Wish I knew what they looked like when they saw their prize plum had left!”

Lestrade breathed out. “But your leg will be fine?”

“Oh, yes sir. Right as rain, ‘e said. First he dug out all the bits of rusted-up metal - that took a while! But first he had to re-open me up as the wound had already started to close... after he finished digging it out he flushed it out with carbolic acid, and then a bottle of silver...” Lions started to lift the sheet to show Lestrade, but the smaller man hurriedly declined the invitation. “And did you know, he even let me watch as he sewed me up. That was right decent of him, I have to allow!” The bushy Constable beamed with pride. “I can now say exactly what it is they did to me - because I saw every bit of it!”

Lestrade did not share that kind of sentiment. “I’m pleased for your peace of mind, Lions. I didn’t think surgeons would release their jealousy long enough to let us laymen in on their trade secrets.”

“Oh, this un, he’s a real bene, sir. Soldier, like. Didn’t believe in treatin’ a grown man like a kitten, but he warned me that if I had to stay on the silver treatment, my skin’d soon go with my uniform!”[18] Lions had half finished his meal. “Said he had a lot of practice back in the war.”

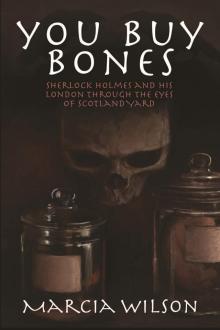

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones