- Home

- Marcia Wilson

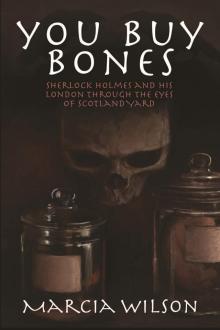

You Buy Bones Page 11

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 11

Bradstreet was a large, gentle man for all that he was fierce in a fight, but Lestrade wished his friend had not had to wear the black so very much. First his sister, then his parents, then an infant... and now his two youngest down from the same fevers and his wife had very nearly followed.

In all but the first case, the passings at least had the comfort of the impartial hand of death. The first one, Bradstreet’s only sister and his closest flesh and blood... had been of willful violence. That was not anything like knowing disease and old age had come calling. It was much worse.

The big man listened in perfect silence, dark eyes intent, never once asking a question. Lestrade was glad when he could finally finish, and the silence steamed between them as Lestrade served up some of Mrs. Collins’ hot coffee and raspberry scones.

Bradstreet chewed through two of those scones, his face wrapped in the deepest concentration Lestrade had ever seen in him. His thoughts were so absorbed he couldn’t even let his emotions out; his eyes clicked like cogs, making Lestrade recall Mr. Holmes was when he was body and soul into a case.

“We had thought of that.” Bradstreet finally said. His mourning-jet cufflinks were dulled with too much recent use; they scraped against the table linen. Lestrade shivered, relieved that the silence was shattered. “There had been a few people who were curious in her... from a... medical viewpoint.” Bradstreet spoke to the top of his coffee, which was muddy and milky and speckled with tiny grounds as if those minute flecks held all the secrets normally revealed by tea leaves. He did not speak to Lestrade. It was easier that way. The years made his face ancient around the lower-mask of his moustache. “I still have the list of names of those who were willing to pay our parents for the honour of examining her.”

“Dr. Watson said he was collating the names of them who were the most outwardly involved.” Lestrade pushed the jam pot to Bradstreet, mostly to give his hands a task.

“Watson has family up there, doesn’t he?”

“I have no idea.” Lestrade confessed. “Why?”

“Well, he’s a Watson.” Bradstreet said as if that explained everything. At Lestrade’s utter blank helplessness, the thinnest smile touched his lips. “Watsons were first registered up there in Edinburgh. Some four hundred years or so... it’s a war-name. Battle commanders. They’re about the worst family you’d ever want to trace, I think there’s about fifty different septs and the Edinburgh strain suddenly vanishes as if it never existed around the first part of our century.

“But as much as the Crown lavishes on its wounded soldiers,” Bradstreet’s second emotion of the day was sarcasm, “I can’t imagine he would have gone up there and paid for a place to stay when there was family to stay with.” He rapped his fingers on the table. “And if he’s so determined to be in on this, I’d say we avoid the fantods for his sake. Anything Watson does for us up there could still cause a backwash to any kith or kin.”

“I hadn’t thought of that.” Lestrade muttered.

“I daresay most your procedural thoughts fled at his news.” Bradstreet said softly.

“Would you rather stay out of this?” Lestrade blurted.

Bradstreet looked amazed. “I am dead until I find my sister.”

“Forgive me, Roger.” Lestrade hated himself.

“Geoffrey...” Bradstreet suddenly looked awkward. He cleared his throat. “Forgive me for asking this... and you don’t have to answer...”

“No, do go on.” Lestrade couldn’t imagine refusing Bradstreet in view of what was happening.

“This could be very dangerous... a doctor who kills for his own glory can do it again. Are you certain you want to be a part of this?”

“Roger, for God’s sake. How could I not be?” Lestrade’s face flared at his embarrassment.

Bradstreet only grunted. “On that sentence... Have you made peace with your kinfolk yet?” He probed.

Lestrade felt words dry in his mouth. It was his turn to speak to the coffee cup. “There doesn’t seem to be much point in my trying any longer.” He said at last. “A rope is a final argument.”

Bradstreet did not compound his confession with words of sympathy. There was no need.

221B Baker Street:

Watson had never before known guilt for poking through Holmes’ papers. Holmes certainly never cared - his only confidential writings were locked up in a trunk half the size of his own bed, and Watson would never touch that. Even if the mercenary urge had come to him, he had every faith it was its own level of organizational Waterloo. But this was the first time he was actually employing Holmes’ own research for a personal matter and it felt vaguely like exploitation.

Just because Holmes had neither rhyme nor reason to his creative filing system, and just because he could never find a blessed thing without covering the carpet in four inches of tossed foolscap, didn’t mean Holmes wouldn’t have a sudden attack of genius on something that was different from the day before. Watson eased the leather binder off the shelf and gave it a stern glare before opening it up.

He sighed hopelessly. Holmes was a neat and hygienic creature when it came to his own skin, but when it came to the way he ordered his life and notabilia... obviously the detective had been smashing all notes under the ‘B’ category in these pages, in no alphabetical order at all, until some sporadic fit of common sense seized him and then he would put everything in order with the paste-pot.

Watson reminded himself that the next time he was trapped inside their apartment he had a new option with which to creatively whittle away his time. He gingerly leafed through two inches of paper, seeking particular names.

The word ‘body-thief’ illuminated itself across his eyes like a cannon’s flare. In another second, he realised he was on the right track. He glanced at the clock. A few more hours before he would be expected at St. ‘Bart’s. If he was careful it would be plenty of time.

He settled down and began to read.

3: Carry a Bone

A dog that will fetch a bone will carry a bone.

-proverb

“Body-thieves”

“...market exists for human remains in part or in whole; market depends on the immoveable factors of 1) an unscrupulous buyer and 2) an equally unscrupulous dealer who is thus in contact with 3) the actual enactors of the crime. The latter is normally among the lowest ranks of London’s social order, somewhat akin to the Celtic sin-eater, and their emotional state is against the hope of redemption. For all their gruesome work, there is a pitiable element to these creatures; they are firmly convinced they exist for Hellfire.

‘The dealer is perhaps the most unscrupulous of the three. It is he that arranges for profit the actions between 1 and 3. He feeds upon the weakness of the buyer, convinces him of the necessity of his law-breaking and his departure from his moral code. His financial stability depends on this skill; you will find him a deceptive fellow, who dresses and acts inside a broad social definition, all the better to blend in with as many different circles as possible. To the buyer, he is deferential and politely subservient; to the hapless body snatcher he is a cold and sadistic bully. The German word schadenfreude, for one who takes pleasure in another’s pain could hardly be more apt...”

(Scrawled in the margins as an afterthought): “Radfahrer: Ger. word for one who browbeats subordinates and flatters superiors...”

Watson lifted his eyes from the fat book and watched tiny grey ice-balls throw themselves against the window-glass. It was a depressing day; he regretted every glance out the window. His subject content did not help his mood or the throb in his knee, which had grown from red and angry to sullen and purple.

His respect for Holmes grew the deeper he worked into the mystery of body-thieves and their world. Holmes had more than the ability to observe the world around him; always he was seeking motive for the actions he noted. There truly was a deep nee

d in him to prove the world was not as nonsensical, random, and illegal as it was often seen. Everywhere he wrote there was an effort to see the underlying cause, the beginning.

Holmes scorned literature, and professed to be ignorant about it even when obscure verse floated trippingly off his tongue to seal a surgical comment upon the conclusion of a case. Watson wondered if he had simply not yet drawn the proper conjecture, for there was the stirring of a true artist in these hasty lines. The overall mood was as evocative as it was gently cautious, informing and warning at the same time. It reminded him a great deal of Rossetti’s Goblin Market, where a young girl tried in vain to warn her sister from the seductions of the freely offered, yet venomous fruits (a greater allegory for the sweetness of danger could scarce be imagined):

“We must not look at goblin men,

We must not buy their fruits:

Who knows upon what soil they fed

Their hungry thirsty roots?”

And yet, for the sensible Lizzie’s efforts, the goblins continued to sing,

“Come buy,”

He wondered how much time the detective had taken to research the reams of paperwork before him - and how slow had his hand been in recording his lightning swift thoughts? Holmes’ hand was not the neatest; the letters often segued into each other in an effort to save time and space on the paper. “Inartistic” a scholar would have decreed, but Holmes was one of the greatest artists Watson had ever hoped to meet.

The doctor rose with a wince, and limped severely to the table where the teapot steamed warm. Holmes would be back within the next two hours. He was well-settled in his task, off on whatever goals his restless mind had driven him to meeting. God alone knew what that would be. Previous experience warned the doctor that his services might be required when he did return - hopefully for mundane purposes, such as a salve against the chafing of a filthy wool disguise, and not the profound, like last month’s split knuckles (Watson had removed a fragment of the foolish attacker’s tooth out of the ring finger). There were times when the faintest perfume of the Jago lingered upon his person but Holmes was too clean to keep a disguise longer than needed, and he scrupulously gave his business to the nearest bath-house when his work in the disease-ridden areas was done. Mrs. Hudson was, of course, quite grateful for the courtesy.

Surely the government would have snapped up his talents had they known of him! His ability to mark people with the objective interest of a chess master would have been invaluable to the military minds and certainly to the political deciders of Britain. What would his life have been then?

No doubt he would have risen quickly to be as famous as a Wellington or Nelson... but goodness knows he would have had to employ a flotilla of secretaries to keep up with him! Watson shuddered at the vivid image in his mind of Holmes with a long-suffering aide-de-camp following in his wake, determining the particulars of battle and then pulling a secret surprise out at the last moment, saving Queen and country.

Watson sighed. When thoughts like that came to his mind, the only cure was a large pot of coffee. He rang the bell and politely requested it of Mrs. Hudson, who, in the light of his room-mate’s routine of bizarre requests, never turned a hair. Tonight he would be at his usual rounds on at the hospital, and caffeine was not normally advised on the onset of a full shift’s labours. But even pretending to rest when he didn’t know of Holmes’ whereabouts was ridiculous. It was easier to rest with a nervous system full of stimulant, knowing Holmes was finally safe, than lie awake ignorant.

St. Bartholomew’s Hospital:

Scotland Yard knew the military man - they’d been led by Colonels and Majors throughout various points in the history of their office. At any given time at least one man in ten had retired from the red uniform to don the blue. It didn’t mean they were like the other men on the force; they had a high drop-out rate; they had ways about them. Ways that were not easily explained, but had to be tolerated.

If forced to explain, everyone would admit resolve and sleeplessness was their greatest common factor.

“Inspectors...”

Lestrade wondered at the look on Watson’s face as he limped down the hallway, folding up a long no-longer white coat marred with terrible looking stains.

“Forgive me,” he said by way of greeting, “we had a terrible mishap at the tracks at dawn.”

“That looks like mud, blood, grass, and... well I’m not sure what that is on you, Watson.” Bradstreet cocked his head to one side and looked the younger man up and down.

“It looks like chalk.” Lestrade guessed slowly. “The cheap kind... like the earth pulled out of Plymouth and used by children.”

“Exactly.” Watson looked down at his clothing. The coat had protected with minimal results. “To be precise, proof that someone was trying to sneak a dark horse in under a pale identity... Are you a fan of the races?”

“Er...” Lestrade was unsure how to proceed. “My family once cherished a fond notion that their son would bring about fame as a jockey.”

“I’ve noticed your hand with horses. Was that the motive?”

“Well, that and the fact that for some time it looked as though I’d never see an inch over five feet.” Lestrade shrugged, suddenly awkward. “I was never so glad as to gain six inches over the mark in my entire life.”

“Couldn’t have made a jockey with your weight anyway, Geoffrey.” Bradstreet rumbled with a grin. He whacked Lestrade on the shoulder with terrific force; the small man barely moved, long used to his larger friend’s ways. “Of course, it means he can’t run as fast as most of us...”

“Can’t have everything, and it’s a small price to pay for not smelling horses all my life.” Lestrade snapped testily.

“I thought you liked the horses?”

“Not that well.” Lestrade muttered. “And I can’t enjoy the races much anymore. I keep thinking of all the criminals that are in the crowds.”

“My greatest crime is an irrational weakness for the underdog at the tracks. It ensures I win no more than one out of six times.” Watson had signaled to an orderly behind Bradstreet. “If you gentlemen have a moment, there is a meeting-room we can use; it’s quite private.”

“By all means lead the way.” Lestrade agreed.

Watson took them to a small room lit with an amazingly ineffectual little fireplace and a stained-glass window made up like a clustre of rosemary, heavy with blue blooms. The murky winter light cast only the palest stripes of colour on the dark paneled wood of the walls and seemed to be at war with the small lamps. Watson picked up a dried wreath of rosemary and placed it on the outer door-knob. A smell reminiscent of roasted lamb or hair-rinse or Christmas floated up.

“A signal,” he explained to their eyebrows. “To anyone else on the floor that a private consultation is taking place and we are not to be disturbed.” He lifted his eyebrows to underscore the point. “Consultation of the bereaved.”

“‘Rosemary, that’s for remembrance.’” Bradstreet quoted the Bard.

Watson chuckled. “Exactly. Nothing short of a fire or an attack by drunken Dynamiters will disturb us now.”

“Neatly done.” Bradstreet heaved himself into the closest chair and let his head fall back with a short puff of breath. “Lestrade’s filled me in on all the details y’gave to him, Watson.”

“I’ve been trying to work a little research into my time,” Watson pulled out his Oxford Street cigarettes, and lit one with great relief. “I confess I’ve been nerve-wracked.” Anyone looking at him would have no trouble believing that; his cheeks were dark with hollows that pulled shadows around his dark eyes. “It somewhat helps a bit that some folk are planning out the first anniversary of the disaster of Maiwand. Everyone seems to look at me and draw their own conclusions for my appearance.” His matter-of-fact statement was a little off the usual demeanor they were used to witnessing.<

br />

“Have you found anything new?” Bradstreet opened his eyes and leveled the uncomfortable doctor with a look. “I can understand your unease, doctor. Please understand, I mourned for my sister years ago. I have always known she was dead, but it was the details I never knew. We are not discussing her; we are discussing her mortal remains, which were the least of her.”

Bradstreet would have made a good soldier. Watson pulled hard on his cigarette. “I learned there were a few men who were willing to make a study of your sister’s condition. One was purely from the nature of a folklorist; the second was from his own work in familial history...” Watson had managed to pull half the cigarette dry in five breaths. “One man had both interests, and a fourth was curious from a private project that studied pathological disease.”

“Disease?” Bradstreet repeated sharply. “She was hardly diseased.”

“Forgive me for not clarifying a point.” Watson stared at his smoke, and then defiantly rose to stand by the chilly little fireplace. A single flame snapped, weak as a wisp. “There are very few causes of polysyndactyly such as your sister’s. The first and most well-known cause is simple inheritance; family traits handed down. All the other causes for this condition tend to be by the influence of rare syndromes or diseases; Mongoloid children, for example, can have the tendency.” He shrugged slightly. “I suspect it is simply inheritance in your family, but I do not have that proof.”

Bradstreet nodded. “It happens in the Roane side of the family off and on. Not so much as one would think, but it’s a bit like... well, a bit like twins popping up. You know it can happen.” He lifted one of his big, normal hands up. “I don’t have a single trait, but let me tell you, I was certain to tell my future Mrs. Bradstreet all about it.” He spread his fingers wide apart. “Luckily she seemed to feel that not a problem, but then she was from the other Roanes.”

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones