- Home

- Marcia Wilson

You Buy Bones Page 10

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 10

“As it should be to anyone with common sense.” Holmes dismissed that with another flick of his wrist. “It is fatally dangerous at worst, and at best... chaotic and illogical. One may only cope by creating an oasis of reason and logic within the city... a depot of commonsense connected by other depots, by which sane people travel.”

“Holmes, how on earth do you do that?”

“Do what, my dear fellow?”

“Manage to... vivisect human nature in such a way. Are you positively certain you never tried your hand at fictional writing?”

Holmes’ snort of feigned outrage was so pure it only made Watson’s amusement grow; by perfect timing Mrs. Hudson emerged with a very heavy tray of hot food against the growing freeze. “Ah, Mrs. Hudson’s famous Red Flannel.” Holmes announced. “Most excellent.”

Watson paused to wonder if Holmes was being so pleasant about his meal because he was trying to jolly his roommate out of his mood. That was a slightly uncomfortable thought, but not one that was easily dismissed. Normally the roles were reversed. And Holmes could say what he would about Scotland Yard; the doctor was aware that the detectives were astonished that it was the nightmare-plagued war veteran with chronic wounds that carried the nurturing role in 221B, and not the man who was still whole-cloth.

As much as he’s smoked today, I’m surprised he even has an appetite; Watson passed the butter to Holmes and searched for the pepper. Perhaps that is a factor to his ignorance of regular meals... I should look into that possibility. If everything I ate tasted of tar and nicotine, I’d hardly want to eat myself...

Holmes was not finished with his new favourite topic. “I would be horrified if you went to work for Scotland Yard.” He informed the other man whilst he poured the hot lemon-water. “Not that the Yard could help but improve by your presence, but the cost would be your mental demotion.”[25]

Watson drew on the reserves of patience he cultivated specifically for Sherlock Holmes - reserves that seemed to grow the more he stretched them. “I promised I would consider the matter.” He pointed out. “For my own peace of mind, I must think of alternatives.” It isn’t as though I’ll get rich with writing my small articles!

Holmes grunted and poured an unhealthy amount of honey into the lemon-water. “That is a bad lot.” He repeated.

“My impression is the men are decent enough.” Watson was beginning to feel his patience stretch to the tearing point.

“Oh, they are decent enough - within their training which is inconsistent in quality and ranges from the abhorrent to the exemplary! Outside of the usual incompetent, one has to be mindful of the unflattering example that is supplementing his meagre income with the usual street-bribes or worse, a palm-greasing for passing information to the higher class of criminal who has the desire and ability to cause genuine harm in London.” Holmes had forgotten his drink in favour of the beef. “Corruption is no more than it is anywhere else, and I assure you, no Inspector who has something to hide comes to me for consultation! I made that very clear when I first started.

“But the lot is bad, Watson. They are bound up in the chains and strait-waistcoats of the system they are sworn to serve, and the rate of losses against justice is simply too high - no, it is not acceptable. For Scotland Yard to stop being a bad lot, it must improve itself from within.”

“Holmes, have you contemplated the possibility you are simply ahead of your time?” Watson wanted nothing more than to savour a stupendous meal, but Holmes had, as usual, grabbed their conversation by the horns and was now driving it bawling down a road with a stick and Watson was along for the show. “Prophecy is often little more than drawing sensible conclusions and solutions to a problem - but just because the solution can be seen does not mean it can be met.”

Holmes grunted. “My dear fellow, logic should be the simplest of all disciplines to master. That no one takes the time to do so in childhood means the human race must inevitably suffer.”

This from a man who didn’t see a reason to try to understand the world around him with a logical, systemic approach in proven sciences like calculus, astronomy, and basic language.

He doesn’t want to know who Thomas Carlyle is... and understanding the man gives one insight to the criminal motive... If I told him one of my own classmates was murdered over a literary scholarship, would he even know what I was talking about? Watson kept his opinion to himself only by a large force of will and a larger forkful of beef. Food made an effective gag. It was easier to keep quiet when he ate. He doesn’t know or care that the earth revolves around the sun... I wish he’d patrol ‘Bart’s with me during the nights of the waxing moon... he’d see for himself the number of births and deaths increase - as well as the shows of mental illness. He might find it a small influencing factor in some of his murder cases... I know I would. There’s a reason why lunacy and mania and moon-struck and moon-calf are all words in the medical dictionary...

Holmes had subsided for the moment inside his vegetables - not that Watson was fooled by this temporary retreat-by-omission. Holmes reminded him of Colonel Hayter in moments like this... he softened one up with the main argument, allowed the enemy to defend themselves, riposted, and promptly withdrew his forces to regroup for the oncoming attack.

I wonder what would happen if I arranged for those two to meet? The thought was undeniably alarming, but also attractive.

2: The Disclosure of a Skeleton

“Never be surprised at the crumbling of an idol or the disclosure of a skeleton”

-John Emerich E. Dalberg

Watson was too worn down from his day to devote attention to both meal and company. Holmes wasn’t in possession of a high level of pride at himself for pressing such an awkward issue when his fellow lodger (or victim) was so low in spirits, but as usual his impulses were at war with his slower-acting caution.

Holmes had seen that look before, when the doctor was tightly gripping to focus on the world around him. When his plate was scoured clean, he rose and went upstairs to change - quite a departure from his normal routine. It was easy to deduce Watson had been at the end of his strength and needed to rest in the sitting room before he went upstairs to actually sleep.

Holmes finished his own dinner with a continuing sense of discomfort and poured out the brandy by the chemistry table. By the time Watson returned, he would have reason to sit by the fire and thaw the freeze that still slowed his movements.

Holmes knew full well what broken bones felt like - and Watson’s bones had been shattered during the war, and it was a poor way to acquire a barometre.

Soon enough, Watson returned looking a bit more human. He blinked in initial surprise as Holmes held the glass out, and then took it with a grateful murmur.

“Not at all.” Holmes waved that off, feeling his ever-present impatience bubble up. Did Watson think he was so self-withdrawn that he would not notice his fellow lodger was dead on his feet and worn to the bone?

Not that, he reminded himself. Watson’s long-term presence was slowly reminding Holmes of the many differences between the way he saw the world, and the way the world thought it worked. In a way it was distraction, but it was instructive. It pulled him outside of the simple intellectual boundaries of his mind and into a much murkier realm of emotion.

He sank back down in his favourite chair, for now not returning to his pipe. Watson had taken the couch, the better to adjust his aching shoulder and a clearly complaining blow to his leg and was half-asleep before the flames.

There was no great intellectual algorithm to that knee; Watson’s balance was not the best with the roads being what they were. It would have been polite to say something, but in the matter of Watson’s recovery, Holmes was resolutely out of his depth. He had never thought of the body as something to use, but the doctor had was a natural athlete; the kind of man who enjoyed pushing his physical limits. Holmes somewhat understood that

drive, though for him it was the thrill of seeing how far his mind could control his body. Afghanistan had tragically left Watson with a frame he barely recognised, and he was still making mistakes in depth and perception.

Holmes had little use for any deep emotions, and these had him troubled on a level on which he did not often see; the Biblical admonition, ‘if thy eye offendeth thee, pluck it out’ reminded him of how Watson sometimes stared down at his stiff arm, or rested his hand on his knee, as if the genuine articles had been stolen whilst he slept and he wondered where the originals were hiding.

Watson had not lied about his nerves, but the greatest enemies are those inside one’s own brain. Holmes had often witnessed the moments of self-castigation in his friend, and the emotion was not far from devout loathing. Whatever had happened in Afghanistan had been the propelling force in his deliberate uprooting of his personal identity. No one simply chose to place themselves in London for the mere sake of it; no, Watson had quit the world he had owned before the military.

Holmes had caught on long ago that Watson’s body was broken, but that was the smaller portion of the problem. Inside that broken body huddled a spirit with something large and precious missing. The clues were as subtle as they were unmistakable; the way the doctor hesitated sometimes, as if something had triggered a memory against his will; there were moments when a thought would occur to him and sever his existing mood. The worst times were when Holmes was a reluctant witness; Holmes would spy Watson in unguarded expressions when the doctor had no suspicion he was being watched.

Who is it he searches for in London? The question alternately flared and smouldered in Holmes’ brain. Why does he not seek them out? It is someone he both needs and dreads.

The silent and painful hope in those brown eyes stymied Holmes, for those thoughts should not be anyone’s business but Watson’s. Watson made no attempts to seek this person out by means of mail, newspaper, Scotland Yard or even the nearest consulting detective who sat at him across the breakfast-table every morning.

He was grateful that they had never needed to speak amongst each other merely for the sake of it; Watson had that rare quality of silence, and days could pass when he barely initiated conversation at all. It was all part of his nature, and Holmes found it a simple thing to live with - his own habits, he was certain, were far stranger and irritating.

There was a price in seeing too much.

“My apologies, Watson.”

Watson had nearly fallen asleep. He lifted his head slightly, drowsy puzzlement tinting his eyes. “Whatever for, Holmes?”

“You are in a low mood and I should not be pressing my opinions on you.” Holmes felt his awkwardness grow, and with it, a converse desire to snap his impatience to the world. “It is clear your day has been as bad as it can get.”

Watson shook them both with a gallows-laugh. “Oh, dear fellow, one never uses those words around a physician. A day can always get worse.” He realised he was in danger of dropping his glass and finished it quickly. “Any day one can walk away can’t possibly be a complete disaster.”

“I feel I prefer your every-day displays of optimism as opposed to that one,” Holmes mused. “But then, most emotions are outside my realm, not just the softer ones.”

Watson opened one eye again, and this time the look was of patient tolerance. “Holmes, it hardly matters. You’ve got a soul and that’s what matters the most.”

Holmes sniggered. “I am often accused otherwise, my dear fellow. I believe it was the Assizes who commented that my curiosity in crime must have been spurned by the grievous theft of my soul as a child, henceforth I dabble in shadows, hoping to find the thief.”

Watson chuckled too, impressed at his wit. “I’m afraid I can’t speak for your childhood. But I can say with confidence you have a soul. Through it your emotions are expressed.” Weariness thickened his voice; with the brandy and the warmth of the fire, he was sliding fast to Morpheus.

“Of course, you had to purchase it first...”

“Purchase it? My dear doctor, I shall have to examine that brandy for foreign agents. “One does not have the ability to purchase a soul.”

“I couldn’t disagree more...” Watson riposted drowsily. “If it’s available from a Tottingham Court Road peddler for fifty-five shillings.”[26]

By the time Holmes had recovered enough to say something, Watson was asleep.

221B Baker Street:

“You won’t find any answers there, my friend.”

Watson slowly released his gaze from his plate to look at his breakfast companion. “I’m sorry; I was woolgathering, Holmes. What did you just say?”

Holmes nodded at the plate. “I was saying you won’t find any answers there - well, at least you won’t find too many. Other than the fact that Mrs. Hudson’s way with sausages are to be commended. They accompany her hand for coddled eggs and toast.”

Watson snorted softly and returned to his fork. “Very true.” He admitted.

Holmes did not quite sigh, but his eyes glittered. “Was the Convention that dreadful?”

Watson’s response was to put down the fork and rest his head in his hands. (Holmes committed himself to an heroic act of will and forced his lips shut) “In some ways, going to that convention was one of the worst mistakes I’ve made in my life.” The doctor confessed.

“And you’ve had the opportunity to make so many mistakes in your advanced years.” Holmes observed.

Watson lifted his head and managed to skewer his room-mate. “In the course of things, Holmes, one doesn’t need to make many mistakes. One is all that’s required.”

“Whilst I’ve often said as much in tracking criminals from those very mistakes, my dear Watson, it is upsetting in the extreme to hear such a philosophy from your lips.” Holmes’ concern, when he was able to express it, could be difficult to combat. “Pessimism does not become you, Watson.”

“You are the philosopher among us, Holmes.” Watson regarded his plate and finally began cutting his food. “I’m the frustrated writer.”

“Better frustrated than frustrating, and that you never are.” Holmes’ sudden desire for neatness led to his using the toast to clean up what remained on his plate.

Watson almost laughed, but it was not the kind of laugh anyone wanted to hear. “What would you say to a doctor who is blood-sick, Holmes?”

Holmes would never admit it to anyone but himself, but Watson had a gift for flattening others with the sheer intensity of his gaze. This was one of those times.

“I would say it is a rare physician who never feels that way.” Holmes picked his words with care; a chasm had yawed open between them, and he was not certain of his path. “One of the finest painters I know cannot bear the sight or smell of his art five months out of the year; an accountant is prone to the silence of a stone two-thirds of his waking day in balance of what he refers to as ‘the chatter of mathematics’ in his head... you have seen for yourself how stale I become when the mood overtakes me.” Holmes abandoned his clean plate for a teacup. “The contradiction of your profession, Watson, is that you as a physician are sworn to uphold life, and yet that oath requires you to be constantly exposed to death and miasma. You would astonish me if you were immune to it.”

Watson appeared to be slightly mollified by Holmes’ observations. “That convention was full of death.” The words were nearly blurted out. “Edinburgh medicine is no light thing, Holmes. It has been holding its own ground among its peers since before it was established in the eyes of the world. I was witness to the most brilliant minds of our time, and I heard their thoughts; saw their demonstrations; came out of it intellectually inspired and encouraged... but that was only the intellectual aspect.

“Perhaps it is because we are still in the wake of war and its strains... but... for every living man there, I swear there was a skeleton, or something

that was once alive preserved in jars. The dissections had never been so hateful to my eye, and I witnessed enough tasteless jokes levity to last a lifetime!” He rubbed at his forehead against the tight band that had appeared. “I don’t remember this when I was a student... can a war change views to such an extent? Where was the reverence?” He finally whispered. “Why was it so rare?”

The doctor had closed his eyes. Holmes could see how his eyes still moved behind the lids, seeing things that had passed. “I can stand being a locum.” He said at last. “I can build on my practice in a year or two, enough that I can purchase something around Paddington or even Kensington... but I tell you Holmes, I see more respect for the dead when I’m with you, or in the cool-room at Scotland Yard.”

Paddington Street:

Bradstreet took the news well, all things considering.

Lestrade had slept as poorly as Watson; every few hours he would catch himself lying wide awake in bed, staring at the black of the ceiling. He would force himself to relax and drift into a doze - but then the enormity of his task would rise up again and undo all the good of the light rest. Bradstreet had commented on it as soon as he’d knocked on the door, as snowmelt evaporated off his blackcloth-broad shoulders like dirty mist.

For all their similarities, Lestrade was not capable of mourning longer than a short period of time. His people were hard-cut children of the Channel Isles and it went against their grain - not to mention their faith - to wear grief heavily. Grief held the dead back from their rightful passage to Heaven. Excessive grief meant their loved ones had to carry heavy buckets slopping over with coal-black tears. At the same time, he understood that Bradstreet’s people weren’t his people, and it stood to reason they’d think and see things differently.

Mourning was a necessity, and one that Lestrade understood even if his own people recoiled from its demonstration. More than expression, Bradstreet was silently advertising that the loss existed. It told people how to act when they were around him - no overt levity, no jokes within a certain frame, nothing that would be inappropriate.

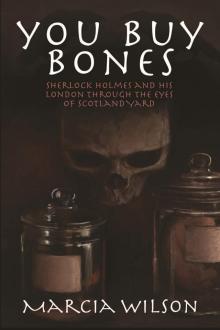

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones