- Home

- Marcia Wilson

You Buy Bones Page 9

You Buy Bones Read online

Page 9

“I had that impression. I came to you because you’ve known him longer, and if it were me, I would need another person with me on such a nightmare.” Watson suddenly remembered his mug and drained it dry. “But I would like to be very clear on this if we are to go further.”

“Speak freely, then.”

“First, do not mention yet how I divined the possible identity of this skeleton.” Watson’s eyes were utterly flat. “I know I am right, but there is no scientific means by which I can prove I am right. Avoid this if we can. We can stick with the physical characteristics that the poor girl was famous for, but let us leave her face out of this. It will be enough if we can prove the murder, or at least his part in it.”

“Completely understandable.” Lestrade agreed with feeling.

“Finally, do what you wish to this monster.” Watson’s face was shadowed in the tavern, and Lestrade was suddenly glad. “But when this is finished and he is behind the bars that own him, I want to speak to him.”

Lestrade swallowed hard. “Easy enough to arrange.” He held out his hand, and the other man shook it. “But if I may inquire upon one small detail?”

“Ask away.”

“Is there a particular reason why you asked me to assist you?” Lestrade had reason to look dubious; he knew better than most that Watson’s notes about the Yard were less than flattering - and the depictions of himself were least of all.

“You worked on a similar case in the past.” Watson said at last. “One of my patients was related to a person who died at the hands of a man you arrested some years ago... you were hailed as being ‘discreet’ and ‘sensitive’ even when it went against the wishes of your officiating Inspector on the job... Carney Ambisinister.”

Lestrade flinched as if struck. In a way, he had been. “Th-that’s an awful business,” he confessed. “For all our efforts, his hand still remains at large. It’s probably in someone’s private Black Mass now.”

Watson was surprised. “I thought you had found the stolen hand.”

“We did... the first time. The second time... the hand was stolen straight out of the Black Museum. Some terrible work of cultists.” He looked down. “We keep a false lure at the Black Museum... hoping someone will grow overconfident and... make a mistake.”

“I see.” Watson let it pass. “When working with such a corrupt mentality, Mr. Lestrade, anything might be possible.”

“Yes,” Lestrade agreed. “...And I’ll speak to Bradstreet. I’m not wholly pleased about the timing of this...” He took a deep breath. “His youngest children left their bodies this winter.”

Watson nodded, his eyes dark and full of meaning. “I would not disturb a man who is already in mourning, were I not convinced of the evidence of my senses.”

“Don’t concern yourself on that.” Lestrade assured him. “It’s... well, it is a personal issue, and it likely will not be a problem.” Now if that wasn’t a lie. “Rest assured, you have welcome news.”

Watson unbent just slightly at that statement, and a cloud broke up in his face. He looked relieved to be listened to... and to be believed.

“Can you give a description of your man?”

“I can do better than that. Look on page 47.” Watson reached into his pocket and withdrew a tiny book - the sort sized for personal convenience. “A Gallery of the Bone Specialists of England. 1879.”

Lestrade went to the directed page and found himself scowling at the printed image of a gentle-faced old fellow with serene, light eyes and thinning hair on a high brow. On the reverse of the page was titled a ‘Quote of Reflection’ and it was from Shakespeare:

“This life,

which had been the tomb

of his virtue and of his honour,

is but a walking shadow; a poor player,

that struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

and then is heard no more:

tis a tale told by an idiot,

full of sound and fury,

signifying nothing.”

“Well, that’s charming.” Lestrade muttered.

Watson made an unkind sound. “If read by a cynical eye, it isn’t the worst of them.” He held up his hand as Lestrade meant to return the book. “Keep it. I have an older copy.” He made an unpleasant twist to his mouth. “He was handing these out as part of his lecture, as he was one of the editors and carried his name upon the title. Our copies were affordable but much abridged. He did of course, have the means to sell us a much more thorough edition if we so chose...” The Doctor failed to look impressed. “He told me this one was his own printer’s proof, and I was already thinking of contacting you... so... I found myself paying more than I really ought for the ownership just so I could get his image in my hands the faster.”

“That’s advertising for you.” Lestrade looked at the name under the face: “Dr. Jonas Q. Parker,” and studied the veritable unchained alphabet running after his name. “He must have a lot of degrees.”

“He gathers a new one every other year.”

“Well, if you’re certain you don’t want it back...”

“Very.” Watson almost snapped. “Keep it. I don’t want it.”

Lestrade felt it might be best to conclude the interview. He took one look outside the tavern’s small windows, gauged the weather, and announced his intention to split the fare home. Watson agreed quickly.

They rode northeast through London in mixed silence as snow whirled before and after their passage. Lestrade’s head was full of conflicting emotions and thoughts as much as was his companion’s. Foremost on the small man’s mind was the troubling instinct that Watson really wanted to avoid Holmes’ involvement out of some sense of... shame.

Shame was not the sort of emotion that belonged on Watson, yet Lestrade didn’t think he was wrong. Watson stared blankly through the wrinkled glass of the window and seemed barely aware of their passage, his brown eyes sinking into the details of the floundering city. Street lamps hissed tired light, and hissed again when the heavy flakes of snow struck the thick glass globes and boxes. Children ran but not for play so much as for money: brooms clutched in lean hands they offered to clear paths for the well-dressed worried for the state of their hems and fine leather shoes. Just off the corner from the University of London’s prestige and glamour, Lestrade recognised its absence in the form of one of the old Crawlers huddled in a door-way. Wrapped head to toe in layers of cloth the old cripple waited for the snow to cover his threadbare woollen cloak, and give him an extra layer of warmth with it.

The cab turned west. The dying light was slanting from the grainy black of floating soot to the pearl-grey of dusk; the clouds collected a brown tint, and the cab began to slow as the flakes flurried in an eye-stinging spray like the ocean. It reminded the little professional a little too much like the ocean, and he spoke to break out of his thoughts, trying to keep the homesickness away before it returned.

“I’ll wire Bradstreet and see if I can’t meet with him early in the morning before his regular work-hours.” The steam from his breath hovered slowly in the cool air.

Watson shifted slightly in the terrible light; the street-lamps added to the lack of visibility, as the illumination was now catching such a blaze of snow one could barely see through the curtain of grey glare. He was relieved when the cab slowed, even if it was worse for his shoulder.

“I am at ‘Bart’s every day if you require a meeting. My morning is mostly the rounds; I usually save the evening for research. You can find me easily enough; the secretary who sits by that large potted pink-lemon tree is my usual contact on where I am and what I shall be doing.”

“That should be easy enough to remember.” Lestrade glanced upward out of habit as the cab slowed. “And here you are...” He slid aside to give Watson room. The doctor stepped out as if his legs had forgotten how to move, clut

ching the edge of the door with his free hand. Lestrade was relieved when he made it safely out. “Tomorrow, doctor.”

Watson waited, leaning on his stick as the cab clopped northwest. His shoulder injury was doing his legs no favours, as it took conscious effort to correct his imbalance when he walked. When his attention wandered, he caught himself walking without proper posture to reduce the vibration of his step into his clavicle. And that, of course, led to an aching, already pained leg on top of an aching shoulder. Vicious circle.

The snow chilled through his shoes. Less than a quarter-hour had passed and half an inch of the lacy stuff had drifted up. Without thinking anything of it, he looked both ways to see if any of those poor Irregulars were running about, but it would appear they had the sense or the means to burrow indoors on a night like this. That felt better. The night was only going to get worse, and even though the boys were a living refutation of the Germ Theory, he still didn’t want them out. There was always the chance Holmes had them out running some kind of godforsaken errand, but he devoutly hoped not.

Holmes really had a lot in common with those children, he mused with a half-smile under his mustache as he crossed the street - walking on eggshells for the lumps of ice he could feel under the snow. If the Irregulars were but a single organism, they would mirror Holmes in so many ways: frantic energy slipping through the worst parts of London; immune to hardship... Watson supposed the only real differences were minor: Holmes donned filth as a disguise that was natural to the boys, and he missed meals because he forgot food, whilst they usually didn’t have a meal to miss in the first place. Otherwise, the two sides were masters in their specialised field of education, and there was a strong possibility that both learned from each other as much as possible.

Watson suspected his friend’s intellect was attracted to the Irregulars for their burning anarchy and ability to be everywhere at once and remain invisible. They were an Army, and he was their King.

A shriek floated up from an alley and Watson realised how very tired he was when his start caused his balance to falter. He slid hard and gnashed his teeth as his knee landed with perfect aim on the top of a cobble. As always, the pain provoked an automatic reaction of blind fury; he pushed himself back up to both feet, leaning a moment on his stick, and listened hard over the pounding of his heart in his ears.

The shriek resounded, and Watson was astonished out of temper to see a rabbit take off from the depths of the alley, a small mongrel hot on its heels. The doctor shook his head in silent wonder. Nothing did quite sound like a frightened hare. What in the world it was doing loose in London was beyond explanation.

London was beyond him.

Calm, now. The middle of the road was no place for such questions. He stepped cautiously, his jaw aching now from the effort of control as now he could claim soreness for three out of four limbs. “Fill all thy bones with aches,” he quoted the Bard sardonically, and breathed easy when he made it to the door of 221B. The anger was melting like the white caps off his shoulders. Another gift from war, to face pain with rage. A full year had passed since his return...

...why was it taking so long to heal?

221B:

Kitchen-smells struck Watson full in the face and he stopped for a moment in the middle of the foyer, breathing in scents that were far from horror: corned beef and beetroots simmered salty sweet odours in the air with sweet-spicy breads. He closed his eyes, reminding himself that the wet, gritty snap of London was now on the other side of the door.

“Oh, there you are, doctor,” Mrs. Hudson emerged with the slightest bit of flour on her hands. That it was there at all was astonishing. “I’ll have supper ready soon. There’s a longer wait on the dessert. This time of year, it’s terrible to wait on the yeast, but I do admit the rising is superior when it is slow.”

Watson breathed in deeply through his nose. “I am perfectly pleased with the wait, if the end result is a portion of what I can smell.” The first of a genuine smile came to his face as he was helped out of his coat. “Mrs. Hudson, you are remarkable.”

“Tush.” She responded with her usual alacrity. “You may thank me tomorrow morning if you are still satisfied.”

He climbed the steps slowly, but at the landing he paused. The sitting-room was much closer than his bedroom, and he would have to come back downstairs anyway. The small dish of curry had burned itself out of him in the cold weather - weather that was growing ever more icy. Yellow light slipped through the door-frame, and he found himself turning the knob.

His fellow lodger was lying with an outward lassitude upon the settee by the fire, a long-stemmed pipe between his lips. Watson looked for the violin, found it safely in its case with the latch open, and felt the disappointment of missed music. Reams of newsprint had fluttered to the floor as sadly as a flock of broken-winged birds. And, worst of all, the tang of some harsh and scorching exotic chemicals touched the back of the doctor’s brain.

A pipe, a Stradivarius, newspapers and chemicals all within a few hours were hardly a reassuring sign as to the mood of the man.

Holmes’ eyes were slipped all but shut, confirming Watson’s suspicion that he had found the outside world wanting, and had reacted by a retreat to the inward one. The way he pulled on the cherrywood resembled too closely the contemplative, sensual and short-sighted pleasures of the opium dens. He must have begun his nicotinic ritual whilst dissatisfied - it appeared to be passing now, by whatever method. Watson glanced at the chemistry table, noting the number of carefully-collected dottles and unburned bits of his day’s pipes. The pre-breakfast smoke was going to be thick tomorrow.

“A pleasant evening with the good Inspector, Watson?” Holmes drawled. “I do hope you’ll take advantage of something besides the curried mutton at the Malmsey Keg someday, my dear fellow. They are quite renowned for their hearty dish of Country Captain,[24] and their spoon bread is all the rage amongst our returning soldiers.”

Watson’s exhausted mind churned through several possible responses, but he knew from experience that whilst Holmes appeared to be generous with his insights, the least discouragement could keep him from talking for well a week. Watson liked the idea of rooming with a statue as much as the next man. “Holmes, I promise you if I was not so utterly exhausted, I would be accusing you of following me about London in the guise of Wiggins! Or was it truly Wiggins I gave the sausage to at noon?” He rubbed bloodshot eyes until the burning sensation faded; and Holmes began laughing around his pipe. Billows of smoke erupted from the corners of his mouth like the seams off a locomotive.

“Ah, you give me credit for my disguises that falls within the fantastic. Not that I’ve never wished for the ability to change my height! If there was some way to surmount that particular problem, I assure you I would be taking advantage of it on a daily basis.” Holmes paused to add another injection of smoke into the room. Watson couldn’t help but notice the haze around the table lamp. “Not a difficult deduction at all... You have brought back a sack of Grozet for your consumption... Inspector Lestrade’s addiction to gooseberry ale is almost a legend among Scotland Yard. The only Grozet that is not guaranteed to send a customer blind, deaf, or dumb - if not temporarily witless - is to be had off Montague Street. Before I found our rooms here, Lestrade would top off his consultations with me by detouring to the Malmsey Keg and washing his annoyances down with at least two pints.” Holmes detached his lips off the pipe long enough to exhale the ghosts of harsh shag. “But I am not privy to all your thoughts, my dear fellow. I for one have no idea what would inspire your collaboration with Lestrade.”

Watson’s mind latched on the nearest available truth. “Lestrade intimated that the Yard is always in need of a police surgeon.” He admitted, and a small part of his psyche was gratified to see Holmes’ eyebrows pop up whilst a frown tightened his chin down - the impression lengthened his entire face. “I am flattered, and I have promised I would

look into it... but at this point in life, I confess I don’t feel very capable of fulfilling such a post.” He nodded downward to his truly-aching shoulder, and honesty coloured his voice.

“My shoulder is still weak; my leg still hurts. A reliable income is always appreciated, but I’d be a liability no matter how they paint it.”

“My dear fellow, your talents would be put to waste at Scotland Yard.” Holmes waved off the whole mess with a flick of his pale wrist, bending his head to his pipe again. Despite the languid - dreamy, even - demeanor, Watson had the distinct impression that Holmes was annoyed straight down to bedrock. “I’ve met the usual lot who stands in for Police Surgeon. If you think Lestrade and Gregson are limited in their intelligence, I submit to you, all thoughts of logical conjecture are starved out in the autopsy rooms.

“And the coroner’s trials? If there is one thing on which I must agree with Gregson and Lestrade, it is the observation that the judges who oversee these trials are pulled out of a most remarkable pool of mediocrity and pedantic intellect. One would have to go to the House of Lords to encounter such deliberate examples of oxygen-starved brain cells.”

Holmes stopped long enough to blow a geometrically graceful smoke ring whilst Watson mourned the fact that Holmes at his verbal best was completely unprintable, unless they both wanted to move to some wretched outpost of the Empire. “Watson, you are better off with a private practice; you know this.”

“Sometimes, I do not know.” Watson wondered that he could deflect Holmes’ attention on to himself by scraping his every last nerve raw on the exposure of his insecurities. But, in a way, Holmes was an excellent conduit for the voice in his head he did not want to listen to. “May I remind you, London is still an unfathomable wilderness to me?”

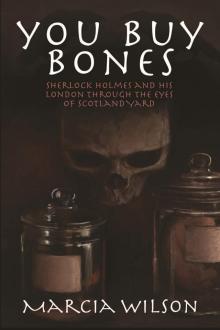

You Buy Bones

You Buy Bones